Acute kidney injury in non-renal medical and surgical admissions in a secondary hospital in Cameroon: recognition and outcomes

Denis Georges Teuwafeu, Arisha Ayonghe, Ronald Gobina Mbua, Clovis Nkoke, Maimouna Mahamat, Mokake Divine, Gloria Ashuntantang

Corresponding author: Denis Georges Teuwafeu, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, Buea, Cameroon

Received: 27 Sep 2021 - Accepted: 03 Dec 2024 - Published: 13 Jan 2025

Domain: Nephrology

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, non-renal medical admissions, surgical admissions, recognition, outcomes

©Denis Georges Teuwafeu et al. Pan African Medical Journal (ISSN: 1937-8688). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Denis Georges Teuwafeu et al. Acute kidney injury in non-renal medical and surgical admissions in a secondary hospital in Cameroon: recognition and outcomes. Pan African Medical Journal. 2025;50:22. [doi: 10.11604/pamj.2025.50.22.31772]

Available online at: https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com//content/article/50/22/full

Research

Acute kidney injury in non-renal medical and surgical admissions in a secondary hospital in Cameroon: recognition and outcomes

Acute kidney injury in non-renal medical and surgical admissions in a secondary hospital in Cameroon: recognition and outcomes

![]() Denis Georges Teuwafeu1,2,&, Arisha Ayonghe2,

Denis Georges Teuwafeu1,2,&, Arisha Ayonghe2, ![]() Ronald Gobina Mbua1,

Ronald Gobina Mbua1, ![]() Clovis Nkoke1,

Clovis Nkoke1, ![]() Maimouna Mahamat3, Mokake Divine2, Gloria Ashuntantang3,4

Maimouna Mahamat3, Mokake Divine2, Gloria Ashuntantang3,4

&Corresponding author

Introduction: there is a paucity of data on the burden of acute kidney injury (AKI) in non-renal medical and surgical admissions where renal function monitoring is not routinely done. This study evaluated the incidence and outcomes of AKI in non-renal medical and surgical admissions at risk of AKI.

Methods: we prospectively assessed non-renal medical and surgical admissions at the Buea Regional Hospital during a 6-week period for AKI risk factors. Consenting participants with AKI risk factors were then screened for AKI using the modified KDIGO (Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes) criteria. We excluded patients with a history of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD), confounders of serum creatinine (e.g. cimetidine, limb amputees), and those without a second serum creatinine value. Modifiable AKI risk factors were corrected and patients with AKI were presented to the nephrologist. Patients were followed up until hospital discharge or death. The outcome measures were the presence of AKI, need and access to dialysis, renal recovery on discharge, for both participants with and without AKI, death, and length of hospital stay.

Results: a total of 165 (41.6% males) participants were included, and six were excluded. The mean (SD) age was 50.7 (17.29) years. Hypertension 43 (26.06%), obesity 28 (16.97%), Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) 25 (15.15%), and diabetes mellitus 22 (13.33%) were the most frequent co-morbid conditions. Sepsis 110 (66.67%) and volume depletion 69 (41.82%) were the most common AKI risk factors. The incidence of AKI was 27.3% (n=45), with 35.6% (n=16) of these in KDIGO AKI stage 3. A total of 4 (8.9%) required dialysis with a 100% access rate. The in-hospital mortality was 6.6% (11/165), with the rate significantly higher in the AKI group (17.78%) compared to the non-AKI group (2.50%) (HR: 2.3, CI: 1.48-2.80, p=0.001). Complications of AKI accounted for 27.27% (3/11) of all causes of death. The median length of hospital stay was longer in the AKI group (11(6-15)) without a statistically significant difference compared to the non-AKI group (8(6-12.5)) (HR: 1.04, CI: 0.99-1.09, p=0.103). Renal recovery on discharge was complete in 62.2% of survivors.

Conclusion: the incidence of AKI is high in non-renal medical and surgical admissions at the Buea Regional Hospital and it is associated with a high mortality.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) which includes acute renal failure is defined as a sudden decline in kidney function (glomerular filtration rate, which results in retention of nitrogenous waste products and disturbances of fluid and electrolyte homeostasis) which can be reversible if detected early [1]. AKI is an increasing public health problem worldwide, associated with adverse outcomes. It is estimated that 13.3 million cases of AKI occur yearly, with 85% occurring in low and middle-income countries [2]. AKI is particularly common in the hospital setting with incidence rates ranging from 22% to as high as 67% in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) [3]. The rates vary from 16.1% to 20% in medical admissions and 18% to 47% in surgical admissions [4-8]. In hospital admissions, AKI increases the length of hospital stay by 5-7 days, the cost of hospitalization by 2 to 3-fold, and the mortality by 6.5-fold [9]. Apart from these short-term outcomes, AKI increases the risk of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) and cardiovascular diseases [10,11]. There is enough evidence to suggest that, late recognition of AKI leads to delay in management leading to increased morbidity and mortality. Deficiencies in AKI care have been reported worldwide. Atiken et al. reported a delay in recognition of AKI in 43% of admitted patients in the United Kingdom (UK) and 24% of cases of AKI were unrecognized in another UK study [12,13]. In a recent nationwide survey in China, the in-time recognition of AKI was low in non-renal medical and surgical departments [3]. There is some evidence suggesting that early diagnosis and timely therapeutic strategies may be the cornerstone of future improvement in outcomes [14].

In Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMIC), outcomes of AKI are severe, with 70% of adults needing dialysis, and a mortality of 32% in adults, which rose to 86% when dialysis was needed but not received [1]. The high mortality rate is a consequence of delays in presentation to health facilities, delays in recognition, and delays in management. In addition, limited access to renal replacement therapy (RRT) due to unavailability and unafordability is a major contributor to the abysmal picture. The access to dialysis in sub-Saharan Africa ranges from 21.4% to 72.2% [15-18]. However, most of the epidemiological data on AKI in LMIC in general and Cameroon in particular stems from observational studies in nephrology units and medical units including renal admissions where selected severe cases are more likely with consequent high need for dialysis and mortality [15-17]. In other non-renal medical and surgical admissions where renal function monitoring is not routine, the true incidence may be higher [19]. This study aimed to determine the incidence, characteristics, and outcomes of AKI in non-renal medical and surgical admissions in a government-funded secondary hospital with haemodialysis facilities.

Study design and setting: this was a 6-week hospital-based prospective cohort study, from March 4th to April 15th, conducted in the medical and surgical units of the Buea Regional Hospital (BRH) in the South West Region of Cameroon. It is a referral hospital for the region and a teaching hospital for medical and nursing students. In addition to outpatient services, it has four main in-patient services: medical, surgical, pediatric, and obstetrics and gynecological units. It also hosts the lone hemodialysis unit of the South West Region. The hospital has several clinical specialists: in the medical ward, there are 2 nephrologists, a cardiologist, and a neurologist, who take part in the day-to-day management of hospitalized patients while in the surgical ward, there is 1 surgeon and 1 orthopedist who take part in the day-to-day management of surgical admissions. The medical ward has a capacity of 40 beds and a patient turnover of about 120 patients monthly. The surgical ward has 23 beds with about 40 admissions monthly. The hospital has a South African National Accreditation System (SANAS) accredited functional laboratory, headed by a laboratory scientist.

Study population: we included all consenting adult non-renal admissions with at least one AKI risk factor [12]. Patients with a known history of CKD, and confounders of serum creatinine such as patients on cimetidine, on cotrimoxazole, limb amputees, crush injury, and those without a second serum creatinine value were all excluded from this study.

We used Cochran´s formula for calculating sample size, the population (p) of AKI in acute medical admissions in a study that screened for AKI risk factors in the UK by Roberts et al. (12.3%) [20]. Therefore, the minimum sample size was 166 participants. The sampling method was consecutive as they were admitted during the period of the study.

Data collection: patients with at least one risk factor of AKI were invited to partake in this study and informed consent was obtained. Variables of interest were socio-demographic including age and sex, clinical parameters including working diagnosis, and comorbid conditions. For each patient, the value of creatinine was obtained using the Jaffe kinetic method at admission and the patient was followed up untill discharge or death. For each patient, the creatinine was repeated after 2 days to 5 days and at discharge. Outcomes of interest were the presence of AKI, need and access to dialysis, length of hospital stay, and renal recovery. Those without AKI were followed up to identify de-novo AKI risk factors. Modifiable risk factors were corrected.

Definition of operational terms: non-renal admissions were defined as patients admitted for reasons not related to the kidney and not from nephrologist consults. Baseline serum creatinine was the first serum creatinine done on identification of AKI risk factor, or a documented serum creatinine value within 7 days. AKI was defined according to the modified Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2012 criteria [21] as an increase or decrease in serum creatinine of 0.3 mg/dl within 48 hours from the baseline. AKI severity was graded using KDIGO 2012 criteria [22].

The need for dialysis was defined as those with indications for dialysis and access to dialysis was defined as those with indications for dialysis that were actually dialyzed. Renal recovery was evaluated at discharge and defined as: 1) complete if normalisation of serum creatinine and; 2) partial recovery if persistence of renal failure without the need of dialysis in those who were receiving dialysis or a decrease in serum creatinine of less than 50% from the value at diagnosis and; 3) no recovery if no decrease in serum creatinine or a decrease of less than 25% or dependency on dialysis.

Ethical considerations: ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board of the University of Buea (2019/898-01/UB/SG/IRB/FHS) and administrative authorizations from the Delegation of Health and BRH. Following a clear explanation of the study in the language best understood by the patient, a consent form was obtained from each patient. The patient was free to withdraw his consent study at any time and no one was sanctioned for not participating. We attributed identification codes to all participants to ensure anonymity throughout the study. We kept the consent forms containing their names separate from the data collection forms. The results of the serum creatinine assay were shared with the participants and the treating physician. All standard procedures during the collection of venous blood samples for serum creatinine assay were respected. This study did not interfere with the procedure of patient care.

Statistical analysis: data was analysed using the statistical package for social sciences software, SPSS version 22.0. Quantitative data was summarized using means (standard deviation) and medians (interquartile range) while categorical data was described using numbers and proportions. The median length of hospital stay was compared between the AKI and non-AKI groups using the Mann-Whitney test. Mortality rates in both groups were compared using the Chi-squared test.

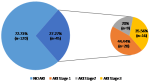

A total of 171 non-renal admissions from the medical and surgical wards were eligible to participate in the study (Figure 1). Six participants were excluded for lack of a second serum creatinine value. Hence, 165 participants were included in the study. The female-to-male ratio was 1.17. The mean (SD) age was 50.7 (17.29) years. Hypertension and obesity were the most frequent co-morbid conditions (Table 1). The main reasons for admission in the medical ward were infections and neurological diseases, with the most frequent pathologies being malaria and cerebrovascular accidents while in the surgical ward, injury, and skin diseases accounted for over 50% of admissions and the most common pathologies were fractures and ulcers (Table 2). The mean (SD) number of AKI risk factors per participant was about three (2.98 ± 1.22). Sepsis 110 (66.67%), volume depletion 69 (41.82%), and use of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blockers 45 (27.77%) age >65 42 (25.45%) were the most common AKI risk factors (Table 3). We found a high incidence of 27.3% of AKI with 35.6% of all cases classified as severe (Figure 2). Of the 45 participants with AKI, 62.2% (n=28) were community-acquired.

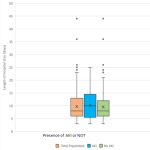

The in-hospital mortality was 6.6% (11/165), with the rate significantly higher in the AKI group (17.78%) compared to the non-AKI group (2.50%) (HR: 2.3, CI: 1.48-2.80, p=0.001). Complications of AKI accounted for 27.27% (3/11) of all causes of death. The median length of hospital stay was longer in the AKI group (11 (6-15)) without a statistically significant difference compared to the non-AKI group (8 (6-12.5)) (HR: 1.04, CI: 0.99-1.09, p=0.103 (Figure 3).

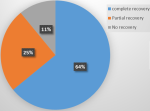

Of the 37 survivors in the AKI group, 23 (62.16%) had complete recovery of renal function on discharge (Figure 4).

In this study, we sought to study the incidence and outcomes of acute kidney injury (AKI) in non-renal medical and surgical admissions in the Buea Regional Hospital. We found a high incidence of 27.3% of AKI, with 35.6% of cases classified as severe. The incidence was significantly higher in non-renal medical admissions, and of the four (8.9%) participants who required dialysis all were dialyzed. We observed a significantly higher mortality rate in the AKI group compared to the non-AKI group (17.8% versus 2.5%, p-value=0.001), while the median length of hospital stay was longer in the AKI group without a statistically significant difference compared to the non-AKI group (11{6-15} versus 8{6-12.5} p=0.103). Renal recovery was complete in 62.2% of survivors in the AKI group.

With the aim of eliminating preventable deaths from AKI by 2025, especially in LMIC, the International Society of Nephrology (ISN) developed the 5Rs that permit timely diagnosis and treatment of potentially reversible AKI for patients [14]. Early recognition of patients at risk for developing AKI is therefore essential to allow early intervention to minimize further renal injury. In this study, a global incidence of 27.3% of AKI was found, with an incidence of 29.5% in the medical unit and 20.9% in the surgical unit. This falls in the range of 22.3% to 35.5% incidence rates described in previous studies from hospitalized patients in Cameroon [15-17]. This finding is in contrast to the pooled worldwide incidence of 21.6% [10]. Lower AKI incidence rates 16.6%-20% were reported among medical admissions, and surgical admissions in other Low- or Middle-Income Country (LMIC) and high-income countries (HIC) [4-8]. The high incidence rates in this study can be explained by the fact that we actively identified and screened non-renal admissions with AKI risk factors. In addition, infectious diseases and sepsis, potent risk factors of AKI accounted for about a third of the reasons for admissions in our study population, increasing the risk of developing AKI. Moreover, 87% of our patients had two or more risk factors, which places them in a cohort of patients at risk of developing AKI [6,20]. Our results are consistent with similar studies in the UK and in the United States, which identified AKI risk factors and routinely screened for AKI, and found incidence rates of 25.55% and 28.8% respectively [7,23]. Roberts et al. reported lower incidence rates of 12.3% in patients at risk for community-acquired AKI in acute medical admissions [20].

In contrast to previous reports in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), we found a low 35.6% incidence of severe AKI (KDIGO stage 3). Reported rates of severe AKI prevalence vary from 48%-77% in LMICs and 41%-47% in HICs [1,24]. In Cameroon, the rate was 59.2% in the same hospital, and 77% in a tertiary hospital [15,17]. Epidemiological studies with a similar methodology to ours revealed lower rates of severe AKI varying from 17.6%-52.5% in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) [11,18,19]. This lower proportion of severe AKI may be explained by the early recognition of AKI through actively screening for risk factors of AKI, monitoring renal function in those at risk, and correcting risk factors among other measures. Other studies were conducted in renal units where patients are referred when the renal failure is already severe. Our results therefore suggest that systematic identification of patients at risk of AKI, and monitoring their renal function reduces the frequency of severe AKI. This finding is important, especially in LMIC where access to dialysis is limited by cost and availability [24]. Consistent with previous reports in Cameroon and other LMICs, AKI was predominantly community-acquired (62%) in contrast to hospital-acquired AKI reported in HIC [1,24]. Community-acquired AKI accounts for over 70% of cases in adults in LMICs, and 40-50% in HIC [24-26]. Olowu et al. reported the prevalence to range from 72.8 to 89.2% in SSA [1].

We noted that 8.9% of patients with AKI required hemodialysis, which is the only modality of renal replacement therapy available at the Buea Regional Hospital. This is much lower compared to the 36% reported in the same hospital and the 50.9% reported in Douala [15,17]. One major explanation for the low rate of dialysis needed in our study is that we identified patients at risk of AKI and routinely screened. As such, AKI cases were detected at an early stage. This reflects the low prevalence of severe AKI as this has been associated with an increased need for dialysis [1]. Our results are similar to Halle et al. 10.1% need for dialysis [16]. Higher rates up to 70% were reported in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. The pooled access to dialysis rate has improved from 17% to 47% in the period 2010-2014 [1]. We found a high 100% access rate to dialysis. The access rate in most sub-Saharan countries is dependent on the availability of a dialysis centre and the ability to pay. Our high access rate reflects the availability of a dialysis centre in the hospital, as well as the subsidized cost of hemodialysis in the country. Relatively lower 66.7% and 72.2% access rates were reported in Buea and Douala, respectively due to lack of funds and adequate materials [16,17]. Olowu et al. reported a 58% access rate in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. In HIC access rates go as high as 100% because of the insurance coverage which subsidizes funds [24-27].

Despite a better understanding of the pathophysiology of AKI, and the advances in medical techniques, AKI has been shown to independently increase in-hospital mortality rate [21,27-32]. AKI multiplies the risk of death by 6 [28]. The reported in-hospital mortality rate of AKI is high varying from 32% to 44.45% [1,5]. Previous observational studies in Cameroon reported high mortality rates of 10.9%-23.5% [15-17]. In this study, we observed an in-hospital mortality rate of 17.8% in the AKI group, which was significantly higher compared to the non-AKI population (2.5%) but consistent with the findings in other African studies with similar study designs. The ISN Global snapshot reported a mortality rate of 13.3% in Africa, and 12% in LMIC [24]. In some unpublished studies with similar designs in Cameroon. The mortality rate ranges from 23.5% in post-operative AKI, 10.9% in pregnancy-related AKI, and 15.6% in the AKI in the ICU. The lower proportion of severe AKI resulting from early recognition and the excellent access in this study may explain the lower mortality as it allows for prompt management of both risk factors and AKI, and consequentially better outcomes [28].

AKI increases the length of hospital stay by 5 to 7 days with the severity of AKI and the need for dialysis being the main drivers of this increase [7,9,23]. We observed a longer median duration of hospital stay of 11 days in survivors with AKI compared to 8 days in those without AKI although this difference did not attain statistical significance. This may reflect the low need for dialysis rate and the low prevalence of severe (stage 3) AKI. About half of our participants with AKI were at stage 1.

Only 50% of patients requiring dialysis will regain normal renal function within 28 days [33]. We observed a 62.2% achievement of complete renal recovery in survivors at discharge. Higher recovery rates were reported when evaluated at 1 month (73%) in Buea and 3 months (84.2%) in Douala [16,17]. Our low recovery rate can be explained by the period we evaluated recovery which was an average of 8 days and reflects our low rate for dialysis needs. Lower rates of 55% were recorded in Douala at 3 months [15]. The younger age population and lower prevalence of severe AKI, which are associated with better outcomes, can explain our higher rate [24,27]. Complete recovery rates of >60% were reported in Low Income Countries (LIC) [1].

Limitations to this study were: the sample size was less than the minimum expected. However, 95% of all non-renal and surgical admissions with AKI risk factors, were included in the final analysis, so our sample is representative. The risk stratification classification we used was obtained from studies done in other LICs and HICs. It is thus possible that we missed out on locally relevant and specific risk factors, thus missing out on some cases of AKI. We evaluated renal recovery on discharge so long-term outcomes in those with partial or no recovery, such as end-stage kidney disease could not be evaluated. The presence of a dialysis centre in the study setting may have contributed to the high access rates to dialysis.

We have shown that the incidence of AKI is high amongst non-renal medical and surgical admissions. The frequency of severe AKI and the need for dialysis are low. Although the mortality rate and length of hospital stay are higher in patients who develop AKI, the rates are better than those reported in observational studies in the same centre. About 60% of those who developed AKI completely recovered their renal function on hospital discharge.

What is known about this topic

- Acute kidney injury (AKI) is particularly common in the hospital setting with incidence rates ranging from 22% to as high as 67% in the ICU;

- The rates vary from 16.1% to 20% in medical admissions and 18% to 47% in surgical admissions;

- In hospital admissions, AKI increases the length of hospital stay by 5-7 days, the cost of hospitalization by 2 to 3-fold, and the mortality by 6.5-fold.

What this study adds

- The incidence of AKI is high amongst non-renal medical and surgical admissions;

- The frequency of severe AKI and the need for dialysis are low;

- About 60% of those who developed AKI completely recovered their renal function on hospital discharge; the mortality rate and length of hospital stay is higher in patients who develop AKI.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Denis Georges Teuwafeu, Arisha Ayonghe, Gloria Ashuntantang, and Maimouna Mahamat were responsible entirely for the conception and design of the study; Arisha Ayonghe, Clovis Nkoke, Denis Georges Teuwafeu, Ronald Gobina Mbua, and Maimouna Mahamat designed data collection tools, collected and monitored data collection for the whole trial, cleaned, analysed, and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript; Denis Georges Teuwafeu, Ronald Gobina Mbua, Arisha Ayonghe, Gloria Ashuntantang, Clovis Nkoke, and Mokake Divine then revised the paper. All the authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Table 1: distribution of socio-demographic characteristics and comorbidity of the study population recruited from the medical and surgical wards of Buea Regional Hospital (BRH) according to sex (N=165)

Table 2: participants diagnosis/causes of admission according to the International Classification of Diseases 11th edition (N=165)

Table 3: AKI risk factor distribution of participants recruited in the medical and surgical wards of the Buea Regional Hospital (BRH) (N=165)

Figure 1: flow diagram of the recruitment of study participants (N=165)

Figure 2: incidence and severity of AKI in the study population

Figure 3: comparison of length of hospital stay between those with and those without AKI

Figure 4: recovery of renal function on discharge

- Olowu WA, Niang A, Osafo C, Ashuntantang G, Arogundade FA, Porter J et al. Outcomes of acute kidney injury in children and adults in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2016 Apr;4(4):e242-50. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Lewington A, Cerda J, Mehta RL. Raising awareness of acute kidney injury: a global perspective of a silent killer. Kidney Int. 2013;84(3):457-67. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Tang X, Chen D, Yu S, Yang L, Mei C; ISN AKF 0 by 25 China Consortium. Acute kidney injury burden in different clinical units: Data from nationwide survey in China. PLoS One. 2017 Feb 2;12(2):e0171202. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Riley S, Diro E, Batchelor P, Abebe A, Amsalu A, Tadesse Y et al. Renal impairment among acute hospital admissions in a rural Ethiopian hospital. Nephrology (Carlton). 2013 Feb;18(2):92-6. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Evans RD, Hemmilä U, Craik A, Mtekateka M, Hamilton F, Kawale Z et al. Incidence, aetiology and outcome of community-acquired acute kidney injury in medical admissions in Malawi. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):21. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Finlay S, Bray B, Lewington AJ, Hunter-Rowe CT, Banerjee A, Atkinson JM et al. Identification of risk factors associated with acute kidney injury in patients admitted to acute medical units. Clin Med (Lond). 2013 Jun;13(3):233-8. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Zeng X, McMahon GM, Brunelli SM, Bates DW, Waikar SS. Incidence, outcomes, and comparisons across definitions of AKI in hospitalized individuals. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 Jan;9(1):12-20. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Carmichael P, Carmichael AR. Acute renal failure in the surgical setting. AZN J Surg. 2003 Mar;73(3):144-53. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005 Nov;16(11):3365-70. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Lameire N, Bagga A, Cruz D, DeMaeseneer J, Endre Z, Kellum J et al. Acute kidney injury: an increasing global concern. Lancet. 2013;382:170-179. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Odutayo A, Wong CX, Farkouh M, Altman DG, Hopewell S, Emdin CA et al. AKI and Long-Term Risk for Cardiovascular Events and Mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017 Jan;28(1):377-387. PubMed | Google Scholar

- National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. Acute Kidney Injury: Adding Insult to Injury (2009). 2009. Accessed 28th November, 2016.

- Aitken E, Carruthers C, Gall L, Kerr L, Geddes C, Kingsmore D. Acute kidney injury: outcomes and quality of care. QJM. 2013 Apr;106(4):323-32. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Mehta R, Cerda J, Burdmann E, Tonelli M, García-García G, Jha V et al. International Society of Nephrology's 0by25 initiative for acute kidney injury (zero preventable deaths by 2025): a human rights case for nephrology. Lancet. 2015;385:2616-43. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Fouda H, Ashuntantang G, Halle M, Kaze F. The Epidemiology of Acute Kidney Injury in a Tertiary Hospital in Cameroon: A 13 Months Review. J Nephrol Ther. 2016;6:250. Google Scholar

- Halle M, Chipekam N, Beyiha G, Fouda H, Coulibaly A, Hentchoya R et al. Incidence, characteristics and prognosis of acute kidney injury in Cameroon: a prospective study at the Douala General Hospital. Ren Fail. 2018;40(1):30-37. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Danielle FM, George TD, Frizt K, Patrice HM, Siysi VV. The Clinical Pattern and Outcomes of Acute Kidney Injury in a Semi-Urban Hospital Setting in Cameroon. J Nephrol Ther. 2018;8(308):2161-0959. Google Scholar

- Effa EE, Okpa HO, Mbu PN, Epoke EJ, Otokpa DE. Acute Kidney Injury in Hospitalized patients at the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital: An etiological and outcome study. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2015;14:55-9. Google Scholar

- Phillips LA, Allen N, Phillips B, Abera A, Diro E, Riley S et al. Acute kidney injury risk factor recognition in three teaching hospitals in Ethiopia. S Afr Med J. 2013 Apr 15;103(6):413-8. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Roberts G, Phillips D, McCarthy R, Bolusani H, Mizen P, Hassan M et al. Acute kidney injury risk assessment at the hospital front door: what is the best measure of risk? Clin Kidney J. 2015 Dec;8(6):673-80. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Wang HE, Muntner P, Chertow GM, Warnock DG. Acute kidney injury and mortality in hospitalized patients. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35(4):349-55. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1-138. Google Scholar

- Challiner R, Ritchie JP, Fullwood C, Loughnan P, Hutchison AJ. Incidence and consequence of acute kidney injury in unselected emergency admissions to a large acute UK hospital trust. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:84. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Mehta R, Burdmann E, Cerdá J, Feehally J, Finkelstein F, García-García G et al. Recognition and management of acute kidney injury in the International Society of Nephrology 0by25 Global Snapshot. Lancet. 2016;387(10032):2017-25. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Bouchard J, Mehta RL. Acute Kidney Injury in Western Countries. Kidney Dis (Basel). 2016 Oct;2(3):103-110. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Naicker S, Aboud O, Gharbi MB. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in Africa. Semin Nephrol. 2008 Jul;28(4):348-353. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Cerdá J, Bagga A, Kher V, Chakravarthi RM. The contrasting characteristics of acute kidney injury in developed and developing countries. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2008 Mar;4(3):138-53. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Bello BT, Busari AA, Amira CO, Raji YR, Braimoh RW. Acute kidney injury in Lagos: Pattern, outcomes, and predictors of in-hospital mortality. Niger J Clin Pract. 2017;20(2):194-199. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Fang Y, Ding X, Zhong Y, Zou J, Teng J, Tang Y et al. Acute Kidney Injury in a Chinese Hospitalized Population. Blood Purif. 2010;30(2):120-6. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Lameire N, Van Biesen W, Vanholder R. The changing epidemiology of acute renal failure. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2006 Jul;2(7):364-77. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Emem-Chioma PC, Alasia DD, Wokoma FS. Clinical outcomes of dialysis-treated acute kidney injury patients at the university of port harcourt teaching hospital, Nigeria. IntSch Res. 2012;2013:e540526. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Lafrance JP, Miller DR. Acute kidney injury associates with increased long-term mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010 Feb;21(2):345-52. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Palevsky PM, Metnitz PG, Piccinni P, Vinsonneau C. Selection of endpoints for clinical trials of acute renal failure in critically ill patients. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2002 Dec;8(6):515-8. PubMed | Google Scholar