Dietary practice and nutritional status of low-income earners in a rural adult population in Delta State, Nigeria: a cross-sectional study

Ogbolu Nneka Christabel, Esegbue Peters, Agofure Otovwe, Okonkwo Browne, Aduloju Akinola Richard

Corresponding author: Ogbolu Nneka Christabel, Department of Public and Community Health, College of Medical and Health Sciences, Novena University, Ogume, Delta State, Nigeria

Received: 10 Jun 2023 - Accepted: 01 Jul 2024 - Published: 29 Jul 2024

Domain: Nutrition,Chronic disease prevention,Health education

Keywords: Nutritional knowledge, dietary habits, dietary condition, low-paid workers, diet, body mass index

©Ogbolu Nneka Christabel et al. Pan African Medical Journal (ISSN: 1937-8688). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Ogbolu Nneka Christabel et al. Dietary practice and nutritional status of low-income earners in a rural adult population in Delta State, Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. Pan African Medical Journal. 2024;48:138. [doi: 10.11604/pamj.2024.48.138.40722]

Available online at: https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com//content/article/48/138/full

Research

Dietary practice and nutritional status of low-income earners in a rural adult population in Delta State, Nigeria: a cross-sectional study

Dietary practice and nutritional status of low-income earners in a rural adult population in Delta State, Nigeria: a cross-sectional study

![]() Ogbolu Nneka Christabel1,&, Esegbue Peters1,

Ogbolu Nneka Christabel1,&, Esegbue Peters1, ![]() Agofure Otovwe2, Okonkwo Browne1, Aduloju Akinola Richard1

Agofure Otovwe2, Okonkwo Browne1, Aduloju Akinola Richard1

&Corresponding author

Introduction: due to the inability of low-income populations to access nutritious foods or basic education, these groups usually consume unhealthy diets, which frequently lead to nutrition issues like obesity, malnutrition, and other health morbidities. The purpose of the study was to evaluate the nutritional knowledge, dietary practices, nutritional status, and factors influencing the dietary habits of low-income persons living in a rural constituency in Southern Nigeria.

Methods: a cross-sectional study was carried out on 419 consenting low-income adults (18 years and older) using a simple random technique, in order to collect data on their socio-demographic traits, nutritional knowledge, dietary practices, and nutritional status. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0 was used to analyze the data generated.

Results: the respondents´ the average age was 40.9 ± 15.68 years while 224 (53.5%) of those surveyed were females. The proportion of responders with a secondary education was highest 279 (66.6%). The most common occupation among respondents was farming 151 (36.1%) and petty trading 135 (32.2%). Overall, 314 (74.9%) of low-income adults had poor dietary habits, and 245 (60.6%) had poor nutrition knowledge. Occupation and gender were significantly associated with nutritional status P<0.05. The majority of respondents 56.2% (235) were overweight or obese, and multivariate logistic regression analysis shows that respondents with concern about gaining weight were more likely to be overweight or obese (OR=1.065, 95% CI=0.832-1.363).

Conclusion: the findings from the study indicate that inadequate nutritional knowledge and poor dietary habits, reflected in respondents' body weight are likely to increase the risk of non-communicable diseases, necessitating the need for nutritional education among rural populations.

The low-income group according to the World Health Organization [1], are those who earn an average of 446,882 naira or an equivalent of $1045 annually while the Federal Republic of Nigeria (1991) defined it as all wage earners and self-employed persons whose annual income in Nigeria is 20% or less of the highest wage grade level's annual maximum income at any given period [2]. Despite global wealth increase, health disparity persists in low-income countries, worsening obesity and malnutrition. According to World Health Organization [1] low-income families (those with an annual or less earning of $1045) consume unwholesome diets than those who earn $12745 or more annually because they barely can afford enough wholesome foods or lack the privilege of basic education which often leads to nutritional disorders like obesity, malnutrition and other health morbidities [3]. Kennedy et al. [4] highlight the lack of fresh fruits and vegetables for a healthy diet in both lower and middle-class families. Low-income communities often sell produce for money, leading to less consumption. Poor nutrition contributes to chronic illnesses like cancer and diabetes, with non-communicable diseases accounting for over 60% of global deaths, with 80% occurring in low-income countries [5,6].

Impoverished communities in countries with low and middle levels of income have been reported to experience a higher burden of chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and nutrition-related NCDs [7]. Nigeria has a stunning rate of 37% nutritional indices which is less than global average making it the world´s second highest. The intake of unhealthy diet and other unhealthy dietary components has caused the rapid emergence of NCDs and the frequency of malnutrition in all its manifestations has been attributed to deficient dietary components, food insecurity, poor socio-economic status, and poor childhood feeding practices among others [8]. In Nigeria, low-income households consume too many calories from staple foods like cassava, rice, yam, and maize and few calories from non-staple foods such as fruits and vegetables, dairy products among others and dependency on these traditional foods has led to nutritional deficiencies as well as NCDs associated with overweight, obesity, diabetes in addition to other cardiovascular diseases [5]. As such, having an understanding of the dietary pattern of low-income households is necessary for the planning and implementation of food and dietary requirement programs [9]. Therefore, the study aimed to determine the dietary practice and nutritional status of low-income earners in a rural adult population in Ndokwa and Ukwuani Local Government Areas of Delta State Nigeria.

Study design and setting: the study employed an exploratory cross-sectional study design that determined the nutrition-related knowledge, dietary practice, and nutritional status of low-income earners in Ndokwa and Ukwuani Local Government Areas of Delta State in Nigeria. Ndokwa/Ukwuani consists of 3 Local Government Areas namely Ndokwa East, Ndokwa West, and Ukwuani. Ndokwa lies between latitudes 50 48´´ N and 50 60´´N and longitudes 60 08´´ E and 60 32´´E of Delta State [10].

Study population: the study population consists of low-income earners in the three local governments that make up Ndokwa/Ukwuani Local Government Area of Delta State. According to the study, low-income earners are those self-employed population male or females which include subsistence farmers, petty traders, vulcanizers, labourers, all those with small scale-sized businesses and without a defined means of livelihood whose annual income is 20% or less of the highest wage grade level's annual maximum income at any given period [2]. The study's inclusion requirements include living in the study area, being self-employed, engaging in subsistence farming, small-scale trading, vulcanization, labour, and any other small-scale business without a defined source of income whose annual income is 20% or less of the highest wage grade level's annual maximum income at any given time. Additionally, participants cannot participate in the study if they have not given their consent. All those who did not meet the inclusion criteria and did not provide consent to participate in the study were excluded from the study.

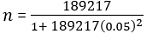

Sample size and sample technique: the Yaro Yamane formula was applied to calculate the sample size based on a 95% confidence level, 5% error horizon, and given the total population of age 20 and above in Ndokwa/Ukwuani Local Government Area to be 189,217 in line with the 2006 population census [11-13].

Where n= sample size; N= population size; e= level of precision or confidence interval ±5% = 0.05; to calculate for Ndokwa/Ukwuani federal constituency with population size 189,217.

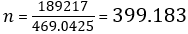

To attribute for the 10% non-response and attrition rate, the size of the sample was adjusted to 444 only 419 responded to the questionnaires giving a response rate of 94.36%. To achieve the number of questionnaires that were distributed across the LGAs, a simple random technique of balloting was employed to choose a community each in the three LGAs. A multi-stage sampling procedure was applied to choose respondents.

Stage one: selection of local government area: Delta State was clustered into 3 senatorial districts which are Delta North, South, and Central. Delta North was randomly picked by balloting and was further stratified into 9 LGA. Ndokwa East, West, and Ukwuani Local Government Area were randomly selected.

Stage two: selection of communities: Ukwuani, Ndokwa East, and West LGAs consist of 9, 10, and 7 communities respectively. Using a simple random approach by balloting method, Amai, Aboh, and Abbi were selected.

Stage three: selection of quarters: Amai, Aboh, and Abbi consist of 5, 5, and 3 quarters respectively. Three-quarters were selected in each community. These quarters were Umuekum, Ishikaguma, and Umuosele of Amai in Ukwuani LGA, Ekwelle, Umeai and Elovei of Abbi in Ndokwa East, and Umu-Ujugbeli, Umu-Ossai, and Umu-Obi of Ndokwa West.

Stage four: selection of houses: all the houses in the three-quarters in each selected community were used for the study.

Stage five: selection of households: only one household (family) in each of the houses in each quarter that were selected across the 3 LGAs was used for the study. If there are two or more households in a house, then the random selection by balloting technique process was adopted to pick a household.

Stage six: selection of respondents: only respondents that met the inclusion criteria (all petty traders, subsistence farmers, and low-scale artisans who were above 18 years) in a household were selected and if there were more than one eligible respondent, only one was chosen using the balloting process.

Ukwani = 60,440 x 444 ÷ 189,217 = 142, since 3 quarters were recruited for the research, 142 ÷ 3= 47. Therefore, 47 questionnaires were given out in the three quarters selected in Amai, Ukwuani LGA. Ndokwa East = 52,524 × 444 ÷ 189,217 = 123, 123 ÷ 3 = 41. Therefore, 42 questionnaires were given out in the three quarters selected in Aboh of Ndokwa-East LGA. Ndokwa-West = 76,253 × 444 ÷ 189,217 = 178, 178 ÷ 3 = 59. Thirty-three questionnaires were given out in the three quarters selected in Abbi of Ndokwa-West LGA.

Method and instrument of data collection: data collection was performed utilizing a detailed semi-structured questionnaire from August 2021 to March 2022. The questionnaire was divided into 4 sections: a socio-demographic characteristic which includes gender, marital status, age occupation, degree of education, and a number of persons in the household, an adapted food and nutrition-related knowledge and dietary practice questions developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation (FAO-UN) [14] and from a previous study [15]. An electronic weighing scale set to the nearest 0.1 kilogram (HANA, Big Boss, China) was used to take their weight, and heights were measured to the closest meter using a tape to be able to calculate BMI according to World Health Organization standard [16] and a section on the variables influencing their food decisions. Information on the frequency of meals-such as the number of breakfasts, lunches, and dinners as well as the practice of skipping meals were obtained. Other information gathered includes information on food preservation techniques, intake of fruits, vegetables, sugar-sweetened beverages, cereals, seafood, beans, and alcohol.

Definitions: knowledge of nutrition: this speaks of people's knowledge and understanding of many aspects of diet and the effects they have. Dietary practices: this comprises patterns of food intake (frequency and types consumed), meal frequency, food sources (homemade versus bought) and status of food security. Nutritional status: the state of a person's health as it relates to the consumption and use of nutrients is referred to as their nutritional status. This may be assessed using the Body Mass Index (BMI) metric, which calculates body fat based on height and weight. Low-income earners: the low-income earners in Ndokwa/Ukwuani Local Government Areas that were utilized for this study included all subsistence farmers, petty traders, vulcanizers, labourers, all those with small-scale sized businesses, and without a defined means of livelihood.

Statistical methods: the retrieved data was analysed with Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Variables were described in descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) and also presented in tables. Pearson's Chi-Square test was utilized to check for statistical variations between the dependent and independent variables. The dependent variable was the nutritional status of low-income earners while the independent variables were their age, gender, occupation, dietary practices, and knowledge. The level of significance for the test of significance was established at P< 0.05, with a 95% confidence range. Logistic regression was used to predict the factors that could influence their dietary practice.

In the scale of measurement, 6 questions were scored on a 12-point weighted scale. Each accurate response received two marks, while non-correct responses received zero. According to scoring and categorizing, respondents with 7 or higher ratings of knowledge were deemed to have strong knowledge, while those with 7 or lower ratings of knowledge were deemed to have poor knowledge. Dietary practice was scored on a 14-point scale and respondents with scores of 7 or higher were thought to have good dietary habits, while those with scores of 7 or lower were seen to have poor dietary habits.

Ethical approval: the Department of Public and Community Health in Novena University, Delta State, first gave permission for the research to be carried out as well as ethical clearance from the Research Ethics and Grant Committee, Delta State University with reference number RBC/FNMC/DELSU/24/330. Following a satisfactory explanation regarding the study, participants gave consent to participate by appending their signature on the questionnaire administered. Additional authorization was secured from the respective community heads who provided letters of approval to that effect.

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents: majority 247 (58.9%) of those surveyed were between ages 20-40, the least 58 (13.8%) were 61 years above and the majority were females 224 (53.5%). Nearly all the respondents 279 (66.6%) attained a secondary education level while the least number of respondents 11 (2.6%) lacked academic training. Among the respondents, 151 (36.0%) were subsistence farmers which means farming was their major source of income and 135 (32.2%) were petty traders (Table 1).

Nutritional knowledge and dietary practice of respondents: the vast majority of participants 338 (80.7%), were unaware of the various food classifications, whereas only 81 (19.3%) were. Two hundred and ninety-six people, or 70.6%, were unaware what a balanced diet was, while only 123 people, or 29.4%, said they understood what it meant. One hundred and eighty-nine people (45.1%) and 230 people (54.9%) respectively knew what a three-square meal was. Furthermore, 393 respondents (93.8%) out of the total respondents knew that diet plays a significant role in disease prevention and management, with 26 respondents (6.2%) making up the smallest percentage. Additionally, a higher proportion of respondents-341 (81.4%)-knew that adults should consume more fruits and vegetables in addition to less red meat, carbohydrates, and fats. While 78 (or 18.6%) are ignorant of this information. Two hundred and fifty-two (252) respondents, or 60.9%, said they knew how to preserve their food the best way, while 138 respondents, or 32.9%, said they didn't. Following additional categorization, it was found that among respondents; nutritional awareness was 60.6% poor and 39.4% good (Table 2).

Among the respondents, 373 (89.0%) expressed a preference for eating meals made at home, while 243 (58.0%) indicated that all meals are significant to them. The most part of respondents 208 (49.6%) eat twice daily, while 179 (42.7%) claimed they never eat three square meals. While 173 (41.3% of respondents) stated they never ate breakfast, 174 (41.5%) said they occasionally did so. Most of the survey participants, 179 (42.7%), claimed they never consume fruits and vegetables. When asked how often they skip meals, 274 (65.4%) said frequently, compared to 226 (53.9%) who had never preserved their food. Furthermore, 292 (69.7%) reported that they consume processed cereal frequently, whereas 210 (50.1%) confirmed that they frequently consume sugar-sweetened drinks. A large majority of individuals (75.7%) from the survey also reported eating fish infrequently, while the majority of participants (77.3%) reported eating meat frequently. Furthermore, among the respondents, 265 (63.2%) frequently eat beans whereas 173 (41.3%) frequently drink alcohol. In general, dietary practice shows that it was 25.1% good and 74.9% poor among the respondents (Table 3).

Factors influencing respondent´s dietary practice: there was no correlation between knowledge and nutritional status, age, and nutritional status at P<0.05 (P=0.951, 0.135), a significant correlation exists between occupation and nutritional status and between gender and nutritional status (P=0.014, P=0.000) respectively. Further results showed factors that affected their dietary practice and multivariate analysis reveals that concern about weight increase (odd ratio=1.065, 95% confidence interval=0.832-1.363) predicted this behaviour (Table 4).

Nutritional status of respondents: nutritional status reveals that 36% (151) of the participants were overweight, 20.8% (87) were obese, 1.9% (8) were underweight and 41.3% (173) had healthy weight.

The main objective of the study was to determine the dietary practice and nutritional status of low-income earners in a rural adult population in Ndokwa and Ukwuani Local Government Areas of Delta State, Nigeria. The findings of the study showed that the study participants demonstrated poor nutritional knowledge, and exhibited poor dietary habits; more than half of the respondents were either overweight or obese, and nutritional status varied across socio-demographic characteristics.

Unhealthy eating practices and poor diet choices have always been considered an underlying reason for poor health status, especially among low-income populations. According to Azizana et al. [17] unhealthy eating practices and poor diet choices among low-income populations have been observed as a prime reason for poor health status.

The research reveals that the majority of respondents are 20-40 years old, with a mean age of 40.9 ± 15.68 years. Females (53.5%) are more likely to live in low-income households than males (46.5%) [18]. Most respondents attended secondary school (66.6%), and the most popular occupations were farming (36.0%) and petty trading (32.2%). This finding is similar to the finding by Afolabi et al. [19] that the most prominent occupations of low-income earners are farming and trading.

Furthermore, more than half of the respondents had poor nutritional knowledge, which could lead to poor dietary habits and health issues. Corroborating with this observation is a study by Sun Y et al. [20] that revealed that a low level of nutrition knowledge increases the potential for chronic diseases and other health problems however this is contrary to previous studies that found good knowledge among chronic disease patients and among low-income residents, women of childbearing age, and older persons [7,21-23]. Differences in socioeconomic characteristics may contribute to these disparities.

It was shown that individuals who frequently drank soft drinks had poor eating habits, which contributed to weight gain and other health problems. A report by Vartanian et al. [24] revealed an obvious connection exists between soft drinks and increased body weight. A high percentage (56.1%) seldom eats fruits and vegetables, this is similar to [17,25] that participants in lower-income households did not consume enough fruits and vegetables necessary for chronic disease prevention. This also corroborates with Heshmat et al. and French et al. [26,27] that families with high socioeconomic status consume more fruits and vegetables and purchase healthier foods than low-income households. In addition, Leone et al. [28] and Huang et al. [29], attributed the poor consumption of fresh produce for those on a limited budget to behavioral and psychosocial factors. Overall, respondents practiced unhealthy eating habits, which was similar to the findings of a previous study by Azizana et al. [17]. Chronic disorders including obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and cancer are associated with poor dietary patterns, which include processed foods, sugar-filled beverages, and saturated fats. They also cause health disparities, higher healthcare expenses, and dietary deficits.

Factors such as culture, religion, taste, time, price, age, income level, weight concerns, income, and knowledge about dietary habits have been shown to influence low-income consumers' dietary choices [22,30-34]. Income does not deter dietary habits although studies have put forward that higher income is connected with improved diet quality, and diet practices, and vice versa [17,27,35-38]. Howbeit a notable factor revealed to be influencing respondents´ dietary habits was concerned weight gain explaining why over 40% of respondents are overweight or obese, which could lead to non-communicable diseases, increased healthcare costs, loss of productivity, and mortality [39,40].

No correlation was found between respondents' knowledge of dietary habits and their nutritional status (0.951). This finding was consistent with previous studies on mixed economic statuses and middle-income populations, which also found no significant association between dietary knowledge and body mass index [41,42]. This implies that improving nutritional status is not always the result of learning about good eating practices. Occupation and nutritional status among respondents showed a significant correlation (0.000), indicating that jobs had an impact on body mass index. Mechanized farming increases obesity risks due to less physical activity compared to traditional farming [43]. Although farmers are physically active, their BMIs are abnormal, suggesting other factors like diet and lifestyle behaviors contribute to their increased BMI [44]. The extent of occupational physical activity also influences overall energy use [43-46]. The creation of interventions, such as workplace wellness programs or nutritional education, for certain occupational groups, might be guided by the relationship between occupation and nutritional status.

A significant association between gender and BMI, with males having normal weight and females being more obese was found. Both genders were underweight, corroborating previous studies showing females in low-income sub-Saharan countries are more obese than males and this disparity is attributed to biological factors such as menopause, cultural values, occupation, and level of physical activity [47]. This is also congruent with Tantut et al. and Muhammad et al. [44,48]. However, Chinedu et al. [49] conducted a survey on young adults and found that females were more overweight, underweight, and obese than males. This highlights the burden of malnutrition and over-nutrition among both genders. The development of gender-specific treatments that meet the particular demands and difficulties faced by men and women can be influenced by the recognition of gender differences in nutritional status. The study found no significant relationship between respondents' age and their BMIs at 0.135. This contradicts a previous study suggesting that aging can lead to poor nutritional status due to impeded food acquisition, digestion, and metabolism [50]. Lastly, the study accounts that 1.9%, 41.3%, 36%, and 20.8% of participants were underweight, healthy, overweight, and obese respectively indicating that those in good physical shape are less susceptible to weight-related health issues, and low-income populations are more susceptible to overweight and obesity [48,51].

By offering a snapshot of food habits and nutritional health at one particular moment in time, the cross-sectional design makes it possible to evaluate correlations between variables and pinpoint possible intervention areas.

Although data was gathered based on respondents' responses, a limitation of this research could be prone to recall bias.

Overweight and obesity is quite prevalent in the communities due to poor socio-economic status. The relatively low number of the participants fell within the recommended healthy weight category however overweight and obesity seemed to be very high. Increased healthcare expenses and a larger illness burden may result from the high incidence of these disorders in low-income populations. One significant factor found to influence their dietary habits was concerns for weight gain and this accounts for why more than 40% of them were overweight and obese which increases cardiovascular disease risk. Healthcare professionals and policymakers should promote nutrition education on the consumption of indigenous fruits and vegetables as well as weight management to prevent malnutrition and chronic diseases.

What is known about this topic

- Improper diets and dietary components are linked to the rapid growth of non-communicable diseases, often leading to malnutrition in all their manifestations;

- Nigerian low-income households are excessively consuming basic and traditional foods, potentially leading to nutritional deficiencies and non-communicable diseases;

- Socioeconomic factors like job, education, and housing stability significantly impact low-income individuals' nutritional status and eating habits, potentially hindering their ability to improve their lives.

What this study adds

- The study documents overweight and obesity among low-income populations making them at risk of cardiovascular diseases;

- Concern for weight gain was an identified factor that influenced their dietary habits;

- Gender plays a significant role in the weight of an individual as women are more likely to be obese and overweight than males.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conception and study design: Ogbolu Nneka Christabel; data collection, entry, and clearing: Esegbue Peters; data analysis and interpretation: Agofure Otovwe; manuscript drafting: Ogbolu Nneka Christabel; manuscript revision: Okonkwo Browne, Aduloju Akinola Richard, and Agofure Otovwe; Ogbolu Nneka Christabel is responsible for the overall credibility of this study. All the authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

The authors recognized the permission granted by the community leaders of the respective communities where this study was conducted.

Table 1: socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents (n=419)

Table 2: nutritional knowledge of the respondents

Table 3: dietary practice of the respondents

Table 4: factors influencing dietary practice of respondents

- World Health Organization. The Global Health Observatory: Income Level. 2022. Accessed 15th February, 2022.

- Olawale SB, Lawal, AA, Alabi, JO. Nigeria Housing Policy: any hope for the poor? American Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences. 2015;1(4):2378-7031. Google Scholar

- Patience S. Supporting Low-Income Families with Nutrition. Journal of Health Visiting. 2013;1(6). Google Scholar

- Kennedy L. The Conversation: Poor diet is the result of poverty not lack of education. 2014. Accessed 25th February 2022.

- Gustafson S. Food Security Portal: Poor Diets Driving Malnutrition in Nigeria. 2020. Accessed 3rd March, 2022.

- Ilori T, Sanusi RA. Nutrition-related knowledge, practice and weight status of patients with chronic diseases attending a district hospital in Nigeria. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11(4):1428-1434. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Boatemaa S, Badasu DM, de-Graft Aikins A. Food beliefs and practices in urban poor communities in Accra: implications for health interventions. BMC Public Health. 2018 Apr 2;18(1):434. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Ene-Obong HN, Alozie Y, Abubakar S, Aburime L, Leshi OO. Update of nutrition situation in Nigeria. The North African Journal of Food and Nutrition Research. 2020;4(9):S63-74. Google Scholar

- Den Hartog AP, Van Staveren WA, Brouwer ID. Food habits and consumption in developing countries. Wageningen Academic Publishers. 2006. Google Scholar

- Okugini NI. Analysis of land use/ land cover change using geospatial techniques in ukwuani local government area of delta state, Nigeria. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science. 2020;4(3):2454-6186.

- City Population. Ukwuani Local Government Area in Nigeria population. 2020. Accessed 3rd March, 2022.

- City Population. Ndokwa West Local Government Area in Nigeria population. 2020. Accessed 3rd March, 2022.

- City Population. Ndokwa East Local Government Area in Nigeria population. 2020. Accessed 3rd March, 2022.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation. Guidelines for assessing nutrition-related Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices. 2014. Accessed 22nd May, 2022.

- Agofure O, Odjimogho S, Okandeji-Barry O, Moses Votapwa. Dietary pattern and nutritional status of female adolescents in Amai Secondary School, Delta State, Nigeria. Pan African Medical Journal. 2021;38:32. PubMed | Google Scholar

- World Health Organization. A healthy lifestyle - WHO recommendations. 2010. Accessed 2nd April, 2022.

- Azizana NA, Thangiaha N, Sua TN, Majida HA. Does a low-income urban population practice healthy dietary habits? Int Health. 2018;10(2):108-115. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Munoz Boudet AM, Buitrago P, Leroy De La Briere B, Newhouse DL, Rubiano Matulevich EC, Scott K et al. Gender differences in poverty and household composition through the life-cycle: A Global perspective. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. 2018 Mar 6(8360). Google Scholar

- Afolabi WA, Olayiwola IO, Sanni SA, Oyawoye O. Nutrient intake and nutritional status of the aged in low income areas of southwest, Nigeria. J Ageing Res Clin Pract. 2015;4(1):66-72. Google Scholar

- Sun Y, Dong D, Ding Y. The Impact of Dietary Knowledge on Health: Evidence from the China Health and Nutrition Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Apr 2;18(7):3736. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Agbozo F, Amardi-Mfoafo J, Dwase H, Ellahi B. Nutrition knowledge, dietary patterns and anthropometric indices of older persons in four peri-urban communities in Ga West municipality, Ghana. Afr Health Sci. 2018 Sep;18(3):743-755. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Evans A, Banks K, Jennings R, Nehme E, Nemec C, Sharma S et al. Increasing access to healthful foods: a qualitative study with residents of low-income communities. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015 Jul 27;12 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S5. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Fasola O, Abosede O, Fasola FA. Knowledge, attitude and practice of good nutrition among women of childbearing age in Somolu Local Government, Lagos State. J Public Health Afr. 2018 May 21;9(1):793. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of soft drinks consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(4):667-675. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Eng CW, Lim SC, Ngongo C, Sham ZH, Kataria I, Chandran A et al. Dietary practices, food purchasing, and perceptions about healthy food availability and affordability: a cross sectional study of low-income Malaysian adults. BMC Public Health. 2022 Jan 28;22(1):192. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Heshmat R, Salehi F, Qorbani M, Rostami M, Shafiee G, Ahadi Z et al. Economic inequality in nutritional knowledge, attitude and practice of Iranian households: the nutria-kap study. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2016 Oct 16;30:426. PubMed | Google Scholar

- French SA, Tangney CC, Crane MM, Wang Y, Appelhans BM. Nutrition quality of food purchases varies by household income: the SHoPPER study. BMC Public Health. 2019 Feb 26;19(1):231. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Leone LA, Beth D, Ickes SB, Macguire K, Nelson E, Smith RA et al. Attitudes Toward Fruit and Vegetable Consumption and Farmers' Market Usage Among Low-Income North Carolinians. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2012;7(1):64-76. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Huang Y, Edirisinghe I, Burton-Freeman BM. Low-income shoppers and fruit and vegetables What do they think? Nutrition Today. 2016 Sep 1;51(5):242-50. Google Scholar

- Kabir A, Miah S, Islam A. Factors influencing eating behavior and dietary intake among resident students in a public university in Bangladesh: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2018 Jun 19;13(6):e0198801. PubMed | Google Scholar

- IvyPanda. Food Habits and Culture: Factors Influence Essay 2020. Accessed 23rd June, 2022.

- Kittler PG, Sucher K, Nahikian-Nelms M. Food and culture. Belmont CA. Wadsworth. 2012. Google Scholar

- Kaya IH. Motivation factors of consumers´ food choice. Food and Nutrition Sciences. 2016;7(3):149-154. Google Scholar

- Miassi YE, Dossa FK, Zannou O, Akdemir S, Koca I, Galanakis CM et al. Socio-cultural and economic factors affecting the choice of food diet in West Africa: a two-stage heckman approach. Discover Food. 2022 May 25;2(1):16. Google Scholar

- Anderson E, Wei R, Liu B, Plummer R, Kelahan H, Tamez M et al. Improving Healthy Food Choices in Low-Income Settings in the United States Using Behavioral Economic-Based Adaptations to Choice Architecture. Front Nutr. 2021 Oct 6;8:734991. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Laraia BA, Leak TM, Tester JM, Leung CW. Biobehavioral Factors That Shape Nutrition in Low-Income Populations: A Narrative Review. Am J Prev Med. 2017 Feb;52(2S2):S118-S126. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Muhammad A, D´Souza A, Meade B, Micha R, Mozaffarian D. How income and food prices influence global dietary intakes by age and sex: evidence from 164 countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2017 Sep 15;2(3):e000184. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Ares G, Machin L, Girona A, Curuthchet RM, Gimenez A. Comparison of motives underlying food choice and barriers to healthy eating among low medium income consumers in uruguay. Cad Saude Publica. 2017 May 18;33(4):e00213315. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Keramat SA, Alam K, Rana RH, Chowdhury R, Farjana F, Hashmi R et al. Obesity and the risk of developing chronic diseases in middle-aged and older adults: findings from an Australian longitudinal population survey, 2009-2017. PLoS One. 2021 Nov 16;16(11):e0260158. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Kearns K, Dee A, Fitzgerald AP, Doherty E, Perry IJ. Chronic diseases burden associated with overweight and obesity in Ireland: the effects of a small BMI reduction at population level. BMC Public Health. 2014 Feb 10;14:143. PubMed | Google Scholar

- O´Brien G, Davies M. Nutrition knowledge and body mass index. Health Educ Res. 2007 Aug;22(4):571-5. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Yu J, Han X, Wen H, Ren J, Qi L. Better Dietary Knowledge and Socioeconomic Status (SES), Better Body Mass Index? Evidence from China-An Unconditional Quantile Regression Approach. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):1197. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Pickett W, King N, Lawson J, Dosman JA, Trask C, Brison RJ et al. Farmers, mechanized work and links to obesity. Prev Med. 2015 Jan;70:59-63. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Tantut Susanto RN, Susumaningrum LA, Siti Ma'fuah BS. Physical Activity and Body Mass Index Among Farmers: A Secondary Data Analysis of Non-Communicable Disease Program at Public Health Center of Jember, Indonesia. International Journal of Caring Sciences. 2022;15(1):134-42. Google Scholar

- Allman-Farinelli MA, Chey T, Merom D, Bauman AE. Occupational risk of overweight and obesity: an analysis of the Australian Health Survey. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2010 Jun 16;5:14. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Suliga E, Ciesla E, Rebak D, Koziel D, Gluszek S. Relationship Between Sitting Time, Physical Activity, and Metabolic Syndrome Among Adults Depending on Body Mass Index (BMI). Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:7633-7645. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Kanter R, Caballero B. Global gender disparities in obesity: a review. Adv Nutr. 2012;3(4):491-498. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Muhammad T, Boro B, Kumar M, Srivastava S. Gender differences in the association of obesity-related measures with multi-morbidity among older adults in india evidence from LASI, wave-1. BMC Geriatr. 2022 Mar 1;22(1):171. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Chinedu SN, Emiloju OC. Underweight, overweight and obesity amongst young adults in Ota, Nigeria. Journal of Public Health and Epidemiology. 2014;6(70):235-238. Google Scholar

- Forster S, Gariballa S. Age as a determinant of nutritional status: a cross sectional study. Nutr J. 2005 Oct 27:4:28. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Kim TJ, Knesebeck OV. Income and obesity: what is the direction of the relationship? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e019862. PubMed | Google Scholar