Prevalence and factors associated with dysmenorrhea in women at child bearing age in the Dschang Health District, West-Cameroon

Axel Mbvoumi Nloh, Esther Ngadjui, Noël Vogue, Aimé Césaire Tetsatsi Momo, Georges Roméo Bonsou Fozin, Yannick Meli Yemeli, Pierre Watcho

Corresponding author: Mbvoumi Nloh Axel, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmaceutical Sciences of the University of Dschang, Dschang, Cameroon

Received: 08 Jul 2019 - Accepted: 09 Oct 2020 - Published: 23 Oct 2020

Domain: Health Research

Keywords: Prevalence, dysmenorrhea, associated factors, Dschang Health District

©Axel Mbvoumi Nloh et al. Pan African Medical Journal (ISSN: 1937-8688). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Axel Mbvoumi Nloh et al. Prevalence and factors associated with dysmenorrhea in women at child bearing age in the Dschang Health District, West-Cameroon. Pan African Medical Journal. 2020;37:178. [doi: 10.11604/pamj.2020.37.178.19693]

Available online at: https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com//content/article/37/178/full

Research

Prevalence and factors associated with dysmenorrhea in women at child bearing age in the Dschang Health District, West-Cameroon

Prevalence and factors associated with dysmenorrhea in women at child bearing age in the Dschang Health District, West-Cameroon

Axel Mbvoumi Nloh1,&, Esther Ngadjui1,2, Noël Vogue1,3, Aimé Césaire Tetsatsi Momo2, Georges Roméo Bonsou Fozin2, Yannick Meli Yemeli1, Pierre Watcho1,2

&Corresponding author

Introduction: dysmenorrhea is a painful phenomenon at the pelvis region preceding or following menstruation. Dysmenorrhea accounts among the most frequent problem of women at child bearing age and affects 45% to 95% of them. According to the WHO, 16.8 to 81% of women are affected by dysmenorrhea. The present study was carried out at the Dschang Health District in order to determine the prevalence of dysmenorrhea and associated factors among women at child bearing age.

Methods: a transversal community-based study was carried out from March to June 2018. Information regarding socio-demographic features, prevalence, factors associated with the dysmenorrhea and the effect of dysmenorrhea on daily activities were collected using structured questionnaire and data were analyzed using Epi Info version 7.1.3.3 Software.

Results: a total of 637 women aged 12 to 50 years were interviewed in the present study. The mean body mass index was 25.94 with an average weight of 66.41 kilogram. 56.20% of participants had dysmenorrhea. From all risks factors fund only the normal body mass index (OR = 3.08, P-Value = 0.01) having a significant association with the occurrence of dysmenorrhea. Daily activities were affected in 73.25% of participants dysmenorrheic and those who had some episodes of dysmenorrhea.

Conclusion: the present study showed that more than a half of respondents were dysmenorrheic and several factors were associated with this pathology. This study also suggests that dysmenorrhea have a negative impact on the daily activities of women at child bearing age.

Dysmenorrhea can be defined as severe, painful and cramp-like sensation at the lower abdomen during menstruation [1]. It may be categorized into primary and secondary dysmenorrhea. Primary dysmenorrhea is menstrual pain without pelvic pathology, with onset typically just after menarch. Secondary dysmenorrhea is menstrual pain associated with a causative pathology [2]. To explain the etiology of primary dysmenorrhea the most accepted theory is the over production of prostaglandins in endometrium during ovulatory cycles [3]. Prostaglandin stimulate the myometrial contractions and local vasoconstrictions that cause the menstrual effluent to be expelled from the uterine cavity [4]. However, secondary dysmenorrhea can be caused by disorders such as endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, intrauterine adhesions or cervical stenosis [5]. There is a wide variation in the estimate of dysmenorrhea from studies around the world.

According to Proctor and Farquhar, the prevalence of dysmenorrhea varies from 45% to 95% depending on the age group [6]. Moreover, the WHO found a prevalence of 16.8 to 81% of women suffering from dysmenorrhea [7]. Dysmenorrhea associated to pelvic pain is one of the most common gynecologic complaints in Women of Child Bearing Age (WCBA) [8, 9]. It is commonly associated to a high rate of absenteeism and low productivity in daily activities. To this important socio-economic dimension is added the psychological impact of the repetitive pain [10]. Dysmenorrhea is therefore a public health problem [4, 11]. In Cameroon, dysmenorrhea is not neglected but very few studies have been done on, especially those relating to the prevalence and associated factors. In accordance with the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) number 3 which aimed at empowering people to live healthy lives and promoting the well-being of all and at all ages [12], the present study was undertaken to determine the prevalence and factors associated with dysmenorrhea in women of childbearing age in the Dschang Health District (DHD).

Study design: a transversal (descriptive and analytic), community-based study was conducted from March to June 2018 in the DHD. Data were collected using a four-part structured questionnaire. An initial survey tested the questionnaire and adapted it to the study population. In this study, the target population was women at child bearing age in DHD and the source population women at child bearing age from 8 Health Areas (HA) of DHD.

Selection Criteria

Inclusion criteria: included in this study were: all girls who experiment menarch and non-menopausal women, aged from 12 to 50 years and agreed to participate.

Exclusion criteria: were excluded from this study, all those expressing the need to stop the interview during data collection.

Sampling

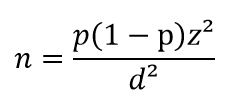

Sample size: sample size was calculated by assuming 95% confidence level, 5% absolute precision or marginal error. Having no prevalence of dysmenorrhea in women of reproductive age in Cameroon in general, and in the DHD in particular, the prevalence of 75% from the study conducted by El-Gilany in Egypt was used [13]. The minimum sample size was then estimated according to Lwanga and Lemeshow [14] as follows:

n = Minimum sample size, Z = 95% confidence level (typical value of 1.96), P = Prevalence of dysmenorrhea, d = Accuracy of the study with margin of error at 5% (typical value 0.05). The minimum value of our sample size was: n = 1.96 x 1.96 x 0.75 x 0.25 / 0.05 x 0.05 = 288.12 ≈ 288 WCBA, thus a cluster effect of 2 gave a sample size for this study of: n = 288 * 2 = 576 WCBA. To account for non-respondents, 10% (non-response rate) was added to this sample size: n + 10% = 576+ (576 x 10/100) = 633.6 ≈ 634 WCBA. The number of clusters being 30, the number of people per cluster was obtained by the following formula:

Population by cluster = 634/30 = 21.13 ≈ 21 WCBA

Sampling method: the sampling method used in this study was the random or probabilistic method, precisely a two (2) degree sampling. The first degree was to choose the number of health areas in the DHD and the second was the selection of 30 villages/quarters to be investigated.

Data collection and treatment: a face to face household questionnaire was administered to participants. Questions regarding socio-demographic features, prevalence, factors associated with the dysmenorrhea and the effect of dysmenorrhea on daily activities of WCBA in DHD were included on this questionnaire. Patients´ weight and height were collected for the determination of Body Mass Index (BMI).

Data analysis: data were analyzed using Epi Info version 7.1.3.3 Software. The prevalence of dysmenorrhea was estimated and the simple logistic regressions of the variables was applied to identify risks factors. After obtaining raw OR and P from simple logistic regressions, the multiple logistic regression of risks factors was done to adjust their ORs and P. The test was significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Ethics considerations: ethical clearance N° 2018/05/1035 / CE / CNERSH / SP was obtained from the National Committee of Ethics of Research for Human Health of Cameroon. An informed consent form or an informed consent read and signed by respondents or parents of minor respondents. Research authorizations had also been obtained from the administrative and traditional authorities. Data confidentiality was firmly followed.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants: during this study, 637 WCBA were interviewed, the age of the respondents ranged from 12 to 50 years. The average age of respondents was 24 years (SD 10.83), 284 (44.58%) WCBA were between 12 and 19 years of age. The minimum weight of the respondents was 38 kg while the maximum was 120 kg with an average of 66.49 kg (SD 12.76). The average height of respondents was 160.03 centimeters (SD 5.81). In the study frequency of respondents based on their BMI show that 298 (46.78%) of WCBA had a normal BMI and 6 (0.94%) had a BMI less than 24.9. This results are showing in Table 1. The distribution of respondents according to their marital status shows that 438 (68.76%) WCBA were single, 59 (24.96%) were married, 25 (3.92%) living in concubine, 6 (0.94%) were divorced/separate and 9 (1.41%) were widow. Concerning medical consultation due to their dysmenorrhea only 99 (25.71%) from 385 dysmenorrheic WCBA and the one who experienced dysmenorrhea before they stopped consulted a medical doctor or health staff.

Characteristics of the menstrual cycle of the respondents: the study revealed that 52.43% of WCBA had their first menses between 13 and 14 years. The Table 1 shows that average age at menarch among the respondents was 13.78 years (SD 1.58). Concerning the duration of bleeding during menstruation 450 (70.64%) of respondents bleeding from 4 to 6 days.

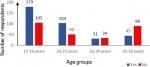

Prevalence of dysmenorrhea in WCBA of DHD: the prevalence of dysmenorrhea among WCBA who participated in this study is shown in Figure 1. It can be noted that 358 (56.20%) suffered from dysmenorrhea. The prevalence of dysmenorrhea by age group is shown in the figure. From this figure we note that 103 (66.88 %) dysmenorrheic respondents were aged 20-25 years old.

Characteristics of dysmenorrhea among respondents: the intensity of perceived pain during their dysmenorrhea is showing in Table 1. In this table 187 (48.57%) reported having moderate pain during menses. Concerning the distribution of WCBA according the duration of pain, from 385 dysmenorrheic WCBA and the one who experienced dysmenorrhea before they stopped, 100 (25.97%) experienced dysmenorrhea during one day and 179 (46.49%) during two days. During the dysmenorrhea some factors could increase the intensity of pain, the study show that of the 385 dysmenorrheal WCBA and the one who experienced dysmenorrhea before they stopped, 104 (27.01%) had an increase of pain when they were stressed, 64 (16.62%) during a school examination period, 50 (12.98%) after school failure, 39 (10.12%) in a family dispute and 27 (7.01%) had an increase in the intensity of pain when they went through a love disappointment.

Signs accompanying dysmenorrhea: from 358 WCBA dysmenorrheal 180 (50.28%) of women felt tired during dysmenorrhea, 174 (48.60%) had abdominal bloating, 164 (45.81%) were irritable, 149 (41.62%) had headache, 137 (38.27%) nausea, 115 (32.12%) dizziness, 110 (30.73%) reported insomnia, 87 (23.30%) reported breast pain, 63 (17.60%) experienced fever, 37 (10.34%) reported diarrhea, 33 (9.22%) had vomit and 46 12,85% (12.85%) had no signs accompanying dysmenorrhea.

Factors associated with dysmenorrhea: the simple logistic regressions of the variables are presented in Table 2. This table shows that risks factors which the highest OR were having a dysmenorrheic mother (OR = 13.56), having a sexual intercourse before the onset of dysmenorrhea (OR = 1.78) and having the BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 (OR = 1.71). After adjustment of risks factors only having BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 have a significant association with the occurrence of dysmenorrhea in WCBA. The multiple logistic regression of risks factors are shown in Table 3.

Effect of dysmenorrhea on the daily activities of respondents: the effect of dysmenorrhea in the daily activities of respondents is shows in Table 4. Out of the 385 dysmenorrheal WCBA and the one who experienced dysmenorrhea before they stopped 282 (73.25%) declared disturbed daily activities during their pain menses while 103 (26.75%) who said their daily activities were not affected.

The present community-based study was conducted from March to June 2018 in the DHD and aimed at determining the prevalence and factors associated with dysmenorrhea in WCBA. A total of 637 WCBA were interviewed and results showed that 56.20% of the respondents were dysmenorrheic. This prevalence is lower than 58.1% found in 2004 in New Zealand [15] and higher than 45% found in 2008 among Nigerian college women [16]. The variation in the prevalence of dysmenorrhea can be attributed to the lack of a universally accepted definition of dysmenorrhea [17] and the variation of socio-cultural and geographical data [18]. Dysmenorrhea affected all group of WCBA from respondent, 63.02% adolescent were dysmenorrheic, prevalence lower than of 65.8% found by Houston [19] and higher than 62.8% found by Rodrigues [20].

Numerous factors may be associated with the occurrence of dysmenorrhea, the one with the highest OR was having a dysmenorrheic mother OR = 3.67 and P = 0.21 are similar to the OR = 2.49 and a P-value = 0.05 obtained by Jaiprakash [21]. Dysmenorrhea can negatively affect women education and socio-professional activities. In this study, 73.25% of the dysmenorrheic had their daily activities disturbed. This frequency is close to the frequency of 86.31% obtained by Narring in Swaziland [9]. Despite these results, the study presents some limits such as; absence of blood analyses of dysmenorrheic respondents in order to evaluate the blood levels of prostaglandin, leukotriene, arginine and vasopressin.

At the end of this study, more than half of the respondents suffered from dysmenorrhea. Factors associated with the onset of dysmenorrhea included but only have BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 have a significant association. Dysmenorrhea has a significant impact on WCBA daily activities, 73.25% of WCBA dysmenorrheal and the one who experienced dysmenorrhea before they stopped in the DHD saw their school, work, social and economic activities disrupted.

What is known about this topic

- Dysmenorrhea are categorized in to types, primary and secondary dysmenorrhea;

- Etiology of primary dysmenorrhea is the over production of prostaglandins in endometrium and the secondary dysmenorrhea can be caused by disorders such as endometriosis and pelvic inflammatory disease;

- WHO found a prevalence of 16.8 to 81% of women suffering from dysmenorrhea.

What this study adds

- To determine the prevalence of dysmenorrhea in WCBA of the DHD;

- To identify the factors associated with the occurrence of dysmenorrhea;

- Finally to determine the frequency of WCBA having their activities disturbed by dysmenorrhea.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Mbvoumi Nloh Axel designed the study, find authorizations for the implementation, collected, analyzed and interpreted data. Participated in the manuscript writing. Ngadjui Esther and Vogue Noël designed the study, find authorizations for the implementation of the study, collected, analyzed and interpreted data. Participated in the manuscript writing. Tetsatsi Aimé Césaire, Momo Georges Roméo Bonsou and Meli Yemeli Yannick collected and analyzed data, participated in the manuscript writing. Pierre Watcho supervised the entire process from the study design to the manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript and equally contributed to its content.

Authors would like to thank the administrative, sanitary and traditional authorities of the Menoua subdivision who facilitated the realization of this study.

Table 1: socio-demographic characters and some characteristics of the menstrual cycle of the respondents

Table 2: simple logistic regressions of factors associated with dysmenorrhea

Table 3: multiple logistic regression of risks factors

Table 4: prevalence of dysmenorrhea and distribution of WCBA according to whether their activities are disturbed by dysmenorrhea

Figure 1: prevalence of dysmenorrhea according to age group

- Pearce JM. Disturbances of the menstrualcycle. In: Varma TR, ed. Clinicalgynaecology. London, 1991; Arnold: 100-117.

- Durain D. Primary dysmenorrhea: assessment and management update. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2004;49(6):520-8. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Deligeoroglou E. Dysmenorrhea. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2000;900:237-244. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Tonini G. Dysmenorrhea, endometriosis and premenstrual syndrome. Minerva Pediatr. 2002;54(6):525-538. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Dawood YM. Dysmenorrhea. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1990;33(1):168-78. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Proctor M, Farquhar C. Dysmenorrhoea, In: Clinical evidence. British Medical Journal. 2004; 11.

- Latthe P, Latthe M, Say L, Gülmezoglu M, Khan S K. WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic pelvic pain: a neglected reproductive health morbidity. BMC Public health. 2006 Jul 6;6:177. PubMed | Google Scholar

- French L. Dysmenorrhoea. Am Fam Physician. 2005 Jan 15;71(2):285-91. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Narring MF, Yaronb A E, Ambresinc. La dysménorrhée: un problème pour le pédiatre? Archives de Pédiatrien. 2012;19:125-130. Google Scholar

- Apter D, Makkonen K. Adolescent health care. Endocrine Development Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2004;7:252-261. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Gordley LB, Lemasters G, Simpson S R, Yiin J H. Menstrual disorders and occupational, stress, and racial factors among military personnel. J Occup Environ Med. 2000 Sep;42(9):871-81. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Nations Unies. Rapport du Groupe de travail ouvert de l´Assemblée générale sur les objectifs de développement durable, Soixante-huitième session. 2014.

- El-Gilany AH, Badawi K, El-Fedaw S. Epidemiology of dysmenorrhoea among adolescent students in Mansoura, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. Jan-Mar 2005;11(1-2):155-63. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Lwanga SK, Lemeshow S. Sample size determination in health studies: a practical manual. World Health Organization, Geneva. 1991; pp: 09-11. Google Scholar

- Grace VM, Zodervan K T. chronic pelvic pain in New Zealand, prevalenc, pain severity, diagnostic and use of health services. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2004 Aug;28(4):369-75. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Loto OM, Adewumi TA, Adewuya AO. Prevalence and correlates of dysmenorrhea among Nigerian college women. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008 Aug;48(4):442-4. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Sultan C, Paris F, Attal G, Legasal P, Lumbroso S, Dumas R. Epidémiologie de la dysménorrhée de l´adolescente en france. In: Sultan C. La puberté féminine et ses désordres. Eska Paris. 2000:219-228. Google Scholar

- Ylikorkola O, Dawood Y. New concepts in dysmenorrhea. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1978 Apr 1;130(7):833-47. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Houston AM, Abraham A, Huang Z, D´Angelo L J. Knowledge, attitudes, and consequences of menstrual health in Urban adolescent females. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006 Aug;19(4):271-5. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Rodrigues AC, Gala S, Neves A, Pinto C, Meireilles C, Frutoso C, Victor ME. Dysmenorrhea in adolescents and young adults: prevalence, related factors an limitations in daily living. Acta Med Port. 2011 Dec;24 Suppl 2:383-88; quiz 389-92. Epub 2011 Dec 31. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Jaiprakash H, Myint KK, Chai LYW, Nasir BM. Prevalence of Dysmenorrhea and Its Sequel among Medical Students in a Malaysian University. British Journal of Medicine & Medical Research. 2016;16(9):1-8. Google Scholar