Prevalence and associated factors of birth defects among newborns in sub-Saharan African countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Fentahun Adane, Mekbeb Afework, Girma Seyoum, Alemu Gebrie

Corresponding author: Fentahun Adane, Department of Anatomy, College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Received: 09 Jun 2019 - Accepted: 20 Feb 2020 - Published: 14 May 2020

Domain: Embryology,Non-Communicable diseases epidemiology

Keywords: Associated factors, birth defects, prevalence, sub-Saharan African countries

©Fentahun Adane et al. Pan African Medical Journal (ISSN: 1937-8688). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Fentahun Adane et al. Prevalence and associated factors of birth defects among newborns in sub-Saharan African countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pan African Medical Journal. 2020;36:19. [doi: 10.11604/pamj.2020.36.19.19411]

Available online at: https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com//content/article/36/19/full

Research

Prevalence and associated factors of birth defects among newborns in sub-Saharan African countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Prevalence and associated factors of birth defects among newborns in sub-Saharan African countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Fentahun Adane1,&, Mekbeb Afework1, Girma Seyoum1, Alemu Gebrie2

1Department of Anatomy, College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2Department of Biomedical Science, School of Medicine, Debre Markos University, Debre Markos, Ethiopia

&Corresponding author

Fentahun Adane, Department of Anatomy, College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Introduction: birth defects are the most serious causes of infant mortality and disability in sub-Saharan African countries with variable magnitude. Hence, this study was aimed to determine the pooled prevalence of birth defects and its associated risk factors among newborn infants in sub-Saharan African countries.

Methods: a total of 43 eligible studies were identified through literature search from Medline (PubMed), EMBASE, HINARI, Google scholar, Science Direct, Cochrane Library and other sources. Extracted data were analyzed using STATA 15.0 statistical software. A random effect meta-analysis model was used.

Results: twenty-five studies in 9 countries showed that the pooled prevalence of birth defects was 20.40 per 1,000 births (95% CI: 17.04, 23.77). In the sub-group analysis, the highest prevalence was observed in southern Africa region with a prevalence of 43 per 1000 (95% CI: 14.89, 71.10). The most prevalent types of birth defects were musculo-skeletal system defects with a pooled prevalence of 3.90 per 1000 (95% CI: 3.11, 4.70) while the least was Down syndrome 0.62 per 1000 (95% CI: 0.40, 0.84). Lack of folic acid supplementation (95% CI: 1.95, 7.88), presence of chronic disease (95% CI: 2.00, 6.07) and intake of drugs (95% CI: 3.88, 14.66) during pregnancy were significantly associated with the birth defects.

Conclusion: the prevalence of birth defects is relatively high with high degree of regional variabilities. The most common types of birth defects were musculoskeletal defects. Lack of folic acid supplementation, presence of chronic disease and intake of drugs during pregnancy were significantly associated with birth defects.

Birth defects (BD) are defined as a series of abnormalities of infants that occur during the pregnancy period. They are described by different terms like congenital disorders, congenital anomalies, congenital malformations and congenital abnormalities [1]. These disorders are classified as structural or functional and can result in critically damaging effects on the lives and health of infants. According to the 2015 report of World Health Organization (WHO), worldwide, congenital anomalies were identified to be the causes of death in about 276,000 newborns under one month of age every year [2]. In 2016, the figure increased to 303,000 neonates [3]. For most of the birth defects, no exact cause(s) have yet been known [3]. However, environmental teratogens, genetic factors and multifactorial inheritance are thought to be the cause of some congenital anomalies [4, 5]. Therefore, investigating these causes and risk factors may help to prevent the anomalies. At present, vaccination, dietary intake of folate or iodine, and preconception health care are available options for prevention [6, 7]. Worldwide, lifelong disability and mortality of children are the outcome of the adverse effects of birth defects. Approximately 3.3 million children under the age of five die per year, because of birth defects. Furthermore, 303,000 infants die within a month of being born because of birth defects, and 3.2 million live-born children are disabled for life, which have direct effect on children, family, health care systems and communities [8]. Although BDs are the most serious cause of infant mortality and disability in both developed and developing countries, around 94% of BDs, 95% of fatalities and 15-30% of hospital admissions of infants and children because of BDs are in low and middle income countries [9].

Worldwide, the prevalence of birth defect varies from region to region. In the United States, it has been expected that birth defects occur in 2.76% of newborns [10]. According to the European observation of Congenital Anomalies (EUROCAT), the general rate of birth defects in Europe was estimated to be 24.86 per 1,000 births during 2010-2014 [11]. In addition, according to the WHO [12] report on population-based registry in Europe the rate of multiple congenital anomalies was 51 per 1,000 live births every year. Based on the WHO report in 2013, the rates of entire structural and functional birth defects in the regions of Eastern Mediterranean and South-East Asia were 69 per 1,000 live births and 51 per 1,000 live births every year, respectively [12]. The prevalence of birth defects among newborn infants were also varied widely in sub-Saharan African countries. It was found to be 1.43 per 1000 in Gabon [13] and 68.4 per 1000 in South Africa [14]. However, there are insufficient reports on the prevalence and associated risk factors of congenital anomalies in sub-Saharan African countries, mainly due to paucity of data from the National Birth Defect Registry. The overall prevalence and associated risk factors of birth defects among newborn in sub-Saharan Africa have not yet been investigated. Therefore, the main aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to estimate the pooled prevalence and to identify the associated risk factors of birth defects in sub-Saharan African countries. The findings of this meta-analysis will help policy makers and other concerned bodies in planning and implementing strategies to prevent birth defects. The study could also be used as a base line for researchers to carry out investigations in related topics. The review question is: what is the best available evidence on the prevalence and associated risk factors of birth defects among newborn infants in sub-Saharan African countries?

Identification and study selection: published articles and unpublished research reporting the prevalence and associated risk factors of birth defects in sub-Saharan African countries were considered. Relevant studies were identified through a literature search of Medline (PubMed), EMBASE, HINARI, Google scholar, Science Direct, Cochrane Library and other sources. The references of each incorporated article were also searched manually to optimize the search strategy. The searching of the articles was performed from the 9th of September, 2018 to the 15th of November, 2018, and it was limited to English. Unpublished studies were also searched from Google and Google Scholar. The key terms used for the search were “Prevalence” OR “Epidemiology” AND “Congenital Abnormality” OR “Congenital Abnormalities” OR “Congenital Malformation” OR “Congenital Anomaly” OR “Congenital Anomalies” OR “Birth Defect” OR “Congenital Disorders”, AND “Each country in the sub-Saharan African region”. All the literatures accessible until November 15, 2018 were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. The systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in agreement with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline [15].

Inclusion criteria: prevalence and associated factors of birth defects in sub-Saharan African countries

Study area: only articles conducted in sub-Saharan African countries.

Study design: all observational studies (cross-sectional, case controls and cohort) that contain original data reporting the prevalence and associated risk factors of birth defects in sub-Saharan African countries were considered.

Language: literatures published in the English language were incorporated.

Population: studies conducted among newborn infants were considered.

Publication condition: both published and unpublished articles which reported the prevalence of birth defects and associated risk factors among newborn infants in sub-Saharan African countries were considered.

Exclusion criteria: non-accessible articles because of un-published, un-retrievable from the internet or failures of reply to correspondences made by e-mail were excluded. In addition, studies, which did not report our outcome of interest, were excluded after reviewing their full texts.

Data abstraction: all the necessary data were retrieved using a consistent data extraction format made in Microsoft Excel. For the prevalence of birth defects, the data extraction format included first author, the country where the study was conducted, and the area of country where the study was carried out, publication year, study design, sample size, and prevalence of birth defects. For types of birth defects the prevalence of neural tube defects (NTD), oral-facial clefts defects (OFC), cardiovascular defects, urogenital defects, Down syndrome, gastrointestinal (GIT) defects and prevalence of unclassified birth defects were also included. For the associated risk factors, the data extraction format was prepared for each specific of the associated risk factor (maternal folic acid supplementation, maternal history of disease and maternal history of medication). We chose these variables because they are the most commonly reported associated risk factors in the studies included in this meta-analysis. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the investigator considered variables as risk factors (maternal folic acid supplementation, maternal history of disease and maternal history of medication) if two or more studies have mentioned them as risk factors. For every associated risk factor, to compute the odds ratio, the data from the primary studies were extracted in the form of two by two tables.

Outcome measurements: this systematic review and meta-analysis have two major outcomes. The primary outcome was prevalence of birth defects among newborn infants in sub-Saharan African countries. The second outcome of the study was risk factors of birth defects in the countries. The prevalence was calculated by dividing the number of infants born with birth defects to the total number of born infants in the study period who have been included in the study (sample size) multiplied by 1000.

Quality assessment: to evaluate the quality of the studies included in this review, the researcher applied the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale tool as modified for cross-sectional studies´ quality assessment [16]. The tool consists of three major parts; the first part has five stars and assesses the methodological quality of each study. The second part of the tool assesses the comparability of the studies. The last part determines the quality of the original articles with respect to their statistical analysis. Using the tool as a checklist, the qualities of each of the original articles were evaluated. Articles with medium (fulfilling 50% of quality assessment criteria) and high quality (≥6 out of 10 scales) were considered to be included for the analysis.

Statistical analysis: the required data were collected using a Microsoft Excel format and analyzed by using STATA Version 15.0 software. The original articles were presented using tables and forest plot. The researcher calculated the standard error of prevalence for each original article by the binomial distribution formula. Heterogeneity among the reported prevalence of studies was checked by using heterogeneity χ2 test, I2 test and the p-values [17]. The above statistic tests indicated that there was a significant heterogeneity among the studies (I2= 97.5%, p < 0.001). As a result, a random effects meta-analysis model was applied to estimate the DerSimonian and Laird's pooled effect. In addition, univariate meta-regression model was conducted by taking publication year and sample size of the studies to discover the probable source of heterogeneity but none of them was statistically significant. Possible publication bias was also evaluated objectively by using Egger's correlation and Begg's regression intercept tests at 5% significant level respectively [18, 19]. The outcome of these assessments proposed that for a likely existence of a significant publication bias (p < 0.001 in Egger's test), the last effect size was determined by using Duval and Tweedie's Trim and Fill analysis in the Random-effects model. Furthermore, to reduce the random discrepancies between the point estimates of the primary study, subgroup analysis was carried out based on region of studies.

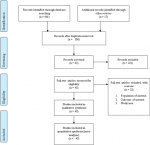

Search results: a total of 958 records regarding prevalence and associated factors of birth defects in sub-Saharan African countries were retrieved from the databases of Medline (PubMed), EMBASE, HINARI, Google scholar, Science Direct, Cochrane Library and other sources described above. From these preliminary records, 672 articles were excluded due to duplication. From the remaining 286 articles, 221 articles were excluded as they were found to be non-applicable to this review after assessing their titles and abstracts. The remaining 65 full text articles were then accessed, and assessed for eligibility based on the preset criteria, which resulted in further exclusion of 22 articles primarily due to the study population and outcome of interest. Among these, fourteen of the studies were conducted in countries other than sub-Saharan African countries: Indian, Iran, Brazil, Canada, China, Italy, Latin America, Pakistan, Spain, Saudi Arabia and Egypt. Three of the studies were conducted in: Tanzania, South Africa and Ugandan and excluded because their study population were not among newborn infants. The remaining five studies were conducted in different parts of Ethiopia and excluded because of the study population and unreported outcome of interest. Finally, 43 studies were found to be eligible and incorporated in the meta-analysis. Among the eligible studies, 25 studies were used for overall prevalence of birth defects. For prevalence of sub type of birth defects, 16 additional studies were included and 2 case control studies were also included for associated risk factors of birth defects (Figure 1).

Characteristics of original articles: Table 1, Table 1 (suite), Table 1 (suite 1), Table 1 (suite 2) summarizes the characteristics of the original articles included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. The study designs for all of the researches were cross sectional study design. Besides, these studies were conducted from 1961 to 2018. The quality score of the researches varied from 6 to 8 out of 10 points. Twenty-five published researches from nine sub-Saharan African countries were used for analysis of pooled prevalence of birth defects. The studies were conducted in Nigeria [20-30], Kenya [31], Tanzania [32], Democratic Republic of Congo [33], South Africa [14, 34-36], Gabon [13], Uganda [37, 38], Ghana [39] and Ethiopia [40-42]. The sample size ranged from 600 in South Africa [35] to 319776 in Ethiopia [42]. The highest prevalence was 85.41 per 1000 in Nigeria [27] while the lowest was 1.43 in Gabon [13]. Fifteen published studies from six sub-Saharan African countries were used for analysis of pooled prevalence of musculoskeletal system defects. The researches were conducted in Nigeria [22-25, 27, 29, 30], Democratic Republic of Congo [33], Tanzania [32], South Africa [6, 34], Kenya [31] and Ethiopia [40-42]. The sample size ranged from 843 in Nigeria [27] to 319 776 in Ethiopia [42]. The highest prevalence was 24.9 per 1000 in Nigeria [27] while the lowest was 0.37 per 1000 also in Nigeria [25]. The remaining types of birth defects are as described in Table 1, Table 1 (suite), Table 1 (suite 1), Table 1 (suite 2). For associated risk factors of birth defects four researches from two sub-Saharan African countries were used. The studies were conducted in Tanzania [43, 44] and in Ethiopia [40, 45] (Table 2).

Meta-analysis

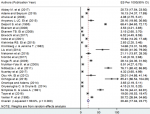

Prevalence of birth defects: twenty five studies in 9 sub-Saharan African countries showed that the prevalence of birth defects was 20.40 per 1,000 births (95% CI: 17.04-23.77) [13, 14, 20-42] (Figure 2). However, considerable heterogeneity was found across the studies as revealed by I2 statistic (I2 = 96.6, p value <0.000). Therefore, a random effect model was used to estimate the pooled prevalence of birth defects in sub-Saharan African countries. A uni-variate meta-regression model was also carried out to identify the possible sources of heterogeneity, by considering factors such as publication year and sample size although none of these variables was found to be statistically significant. However, Beggs' and Eggers' tests exposed the presence of statistically significant publication bias of p = 0.008 and p = 0.044, respectively. Thus, Trim and Fill analysis were performed to correct the final pooled estimate.

Subgroup analysis: in this meta-analysis, subgroup analysis was carried out based on the regions where the studies were conducted. The highest prevalence was observed in Southern Africa region with a prevalence of 43 per 1000 (95% CI: 14.89, 71.10) followed by Central African 30.74 per 1000 (95% CI: 19.47, 42.01), Eastern Africa 17.30 per 1000 (95% CI: 7.77, 26.82) and Western Africa, 9.17 per 1000 (95% CI: 7.14, 11.20) (Figure 3).

Types of birth defects: among the types of birth defects in sub-Saharan African countries, the most frequent types of BD were musculoskeletal systems defects with a pooled prevalence of 3.90 per 1000 (95% CI: 3.11, 4.70), followed by neural tube defects 2.98 per 1000 (95% CI: 2.25, 3.71), cardiovascular system defects (CVSDs) 2.83 per 1000 (95% CI: 1.56, 4.11), gastrointestinal defects 1.50 per 1000 (95% CI: 1.00, 2.01), oro-facial clefts (OFCs) 1.27 per 1000 (95% CI: 1.6, 1.48), unspecified birth defects 0.86 per 1000(95% CI: 0.38, 1.34), urogenital system defects 0.69 per 1000 (95% CI: 0.47, 0.91) and Down syndrome 0.62 per 1000 (95% CI: 0.40, 0.84) (Table 3).

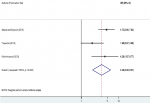

Factors associated with birth defects: the associations of maternal folic acid supplementation, maternal illness and maternal history of medication during pregnancy with birth defects were analyzed in four analyzable studies [40, 43-46]. Sensitivity analyses were also performed for each of the factors, but none of these was found to be significant. Therefore, from the four studies, we found that maternal folic acid supplementation during pregnancy was significantly associated with birth defects among newborn infants, odds ratio 3.92 (95% CI 1.95, 7.88) (Figure 4). In epidemiological expressions, this shows us that infants born from mothers who did not have folic acid supplementation during pregnancy were 3.92 times more likely to have birth defects as compared to those who had folic acid supplementation during pregnancy. Three studies also pointed out that the presence of maternal illness during pregnancy was significantly associated with the birth defects among born infants, odds ratio 3.48 (95% CI 2.00, 6.07) (Figure 5). This implies that infants of mothers who had a disease during pregnancy were 2.19 times more likely to have birth defects. Finally, two studies showed that maternal history of medication during pregnancy was significantly associated with birth defects among born infants, odds ratio 7.54 (95% CI 3.88, 14.66) (Figure 6). This indicated that infants of mothers who took drugs during pregnancy were 7.54 times more likely to have birth defects.

This meta-analysis is the first of its kind in sub-Saharan African countries to estimate the pooled prevalence and associated risk factors of birth defects among newborn infants. The study has found that the overall prevalence of birth defects in sub-Saharan African countries among newborn infants is 20.4 per 1000 (95% CI: 17.04, 23.77%). This finding is in line with a study in the northeast region of Cairo, Egypt, which has reported a BD prevalence of 20 per 1000 [46] among newborn infants and children. However, the prevalence of BDs observed in the present study is slightly less than another study conducted in Europe which reported prevalence values of 23.9 per 1000 and 24.86 per 1000 [11, 47]. A higher prevalence of birth defects with 41 per 1000 has been described in a study performed in Pakistan [48]. Furthermore, based on the WHO report in 2013, the rates of total structural and functional birth defects were higher in the regions of Eastern Mediterranean and South-East Asia with a respective prevalence rates of 69 per 1,000 and 51 per 1,000 live births every year [12]. There could be several reasons for the heterogeneity of the prevalence rates among the various studies as compared with the present study. Higher prevalence rates of BD in those studies in Europe may be due to well organized and better birth registry system compared to sub-Saharan African countries. As a result, the possibility of data loss may be greater in sub-Saharan African countries than Europe. Difference in study design, population sampling and ethnicity may also be factors that contribute for the higher prevalence rates in the above studies. On the other hand, a lower frequency of birth defects (12.5 per 1000 live births) has also been reported by a research carried out in India where the data were collected from a smaller sample size in a single hospital [49].

The subgroup analysis of this study showed that the prevalence of birth defects among newborn infants significantly varies across regions of the sub-Saharan African countries. The highest prevalence of birth defects was observed in Southern Africa region, 43 per 1000 (95%CI: 14.89, 71.1%) followed by the Central Africa region, 30.74 per 1000 (95% CI: 19.47, 42.01%) and Eastern Africa 17.3 per 1000 (95% CI: 7.77, 26.82%), while the lowest prevalence was observed in the Western Africa region with a prevalence of 9.17 per 1000 (95%CI: 7.14, 11.2%). The present finding is in trajectory to the report of the study conducted on the prevalence of common birth defects in South African infants [34]. This might be because of the reason that birth defect is a principal disorder which is much more common in the South African black populations as found by Stevenson AC [50]. This could be explained by the fact that in South Africa environmental teratogens are much more common than other sub-Saharan African countries. It is because of better economic status of South Africa than other sub-Saharan African countries. The other possible justification for this discrepancy could be due to the variation in sample size for the different studies conducted across the regions.

The most common types of birth defect were musculoskeletal systems defects followed by neural tube defects while the least frequent were urogenital system defects and down syndrome. Comparable sequence of the organ system defects have been described in a study conducted in southern Vietnam and where the most common types of BD were musculoskeletal system defects [51]. However, in a previous systematic review and meta-analysis on types of birth defects conducted in Iran [52], urogenital anomalies were the most frequent type of birth defects. This could be explained by the fact that the risk factors for the type of birth defects may vary from region to region [12]. The present study shows that there are significant associations between the prevalence of BDs and maternal history of medication during pregnancy, lack of maternal folic acid supplementation and presence of chronic disease during pregnancy. Infants born from mothers who have history of medication during pregnancy were 7.54 times more likely to have a birth defects compared to infants born from mothers who did not have history of medication drug during pregnancy. This finding is in line with that of another study which reported that maternal use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs during pregnancy is a risk factor for congenital anomalies [53]. It is also supported by an experimental study conducted to evaluate the toxicological consequences of chloroquine and ethanol on the developing rat fetus which has shown a teratogenic effect of anti-malarias causing structural birth defects such as cleft palate, wrist drop, clubbed foot and brain liquefaction [54]. It, therefore, appears that pregnant women taking both prescribed and non-prescribed drugs which have the ability to pass through placental barrier may disturb the normal organogenesis and histogenesis of the developing embryos as suggested by Nelson MM and Forfar JO [55].

Infants born from mothers who had no folic acid supplementation during pregnancy were 3.92 times more likely to have birth defects compared to those born from mothers who had folic acid supplementation. This finding is in line with a study which reported that folic acid supplementation lowers the risk of birth defects [56]. The present finding is also in agreement with a study conducted in Texas, which reported that maternal folic acid supplementation considerably reduces the magnitude of NTDs [57]. Maternal folic acid supplementation, particularly one month before conception and all over the first trimester, appreciably diminishes BDs, primarily NTDs [58-61]. This could be explained by the fact that folic acid supplementation with vitamin B12 is very important for the synthesis of nucleic acid, lipids, and proteins, necessary for cell division, differentiation and migration [62, 63]. Iron folate/folic acid is also very important in amino acids metabolisms that are required for DNA and RNA synthesis and plays an important role as an antioxidant agent. As a result, it is necessary to make folic acid accessible to all pregnant women to prevent birth defects [62].

Infants born from mothers who had a disease during pregnancy were 3.48 times more likely to have birth defects as compared to infants born from mothers who did not have diseases. The presence of maternal illness during pregnancy as a risk factor for birth defects is previously acknowledged by other study [64]. The present result is also in line to the systematic review and meta-analysis which have reported previously as maternal obesity and gestational diabetes are risk factors for birth defects [65, 66]. This may be explained by the fact that maternal chronic disease like hypertension and diabetes during pregnancy compromises utero-placental circulation, which affects the development of the embryo [67]. Hypertension during pregnancy had also been implicated to significantly increase the risk for other birth defects like congenital heart disease, hypospadias and esophageal atresia/stenosis [67-69].

Strength and limitations of the study: the strength of this meta-analysis is the first of its kind in sub-Saharan African country and it lies in the quest of existing and unpublished research and the use of several thoughts to digest the study. However, all articles found to have been cross-sectional in nature in this systematic review and meta-analysis. As a consequence, it is not possible to establish temporal relations between factors and outcome variables. Most of the research included in this review had a small sample size that could influence the final estimate. Furthermore, since this meta-analysis included accessible research recorded from a small region in sub-Saharan African countries, the various countries in the study area may be under-represented.

The present review has revealed a relatively high prevalence of birth defects among newborn infants in sub-Saharan African countries. The most common types of birth defect were musculoskeletal defects, followed by neural tube defects, cardiovascular system defects, gastrointestinal defects and oro-facial clefts (OFCs). Lack of folic acid supplementation, presence of chronic disease and intake of drugs during pregnancy were significantly associated with birth defects. Therefore, based on the findings, it is recommended that efforts should be made to ensure that women use folic acid during the periconceptional period and during pregnancy. In addition, drugs should cautiously be prescribed to pregnant women, and chronic diseases of women must properly be managed so as to minimize the occurrence of birth defects. Furthermore, given the high prevalence of birth defects shown in this review, it is recommended that Fetal Medicine Unit maybe functional in the countries.

What is known about this topic

- Birth defects are a major public health challenge worldwide, especially in developing countries including Ethiopia;

- Different and few studies have been conducted in the study area;

- The problem is still higher and abundant discrepancy and inconstancy among sub-Saharan African countries.

What this study adds

- The prevalence of birth defects in sub-Saharan African countries among newborn infants is 20.4 per 1000;

- The most common types of birth defect are musculoskeletal systems defects;

- Maternal history of medication during pregnancy, lack of maternal folic acid supplementation and presence of chronic disease during pregnancy are the factors associated with birth defects.

The authors declare no competing interests.

FA involved in the design, selection of articles, data extraction, statistical analysis and manuscript writing. MA involved in selection of articles, statistical analysis and manuscript editing. AG and GS were also involved in data extraction, analysis and manuscript editing. All the authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

We would like to articulate our thankfulness and appreciation to all Addis Ababa and Debre Markos University College of Medicine and Health Sciences staffs that supported us in this review.

Table 1: descriptive summary of 25 studies reporting the prevalence of birth defects and additional studies reporting the prevalence of sub types of birth defects among newborn in sub-Saharan African countries included in the systematic review and meta-analysis

Table 1 (suite): descriptive summary of 25 studies reporting the prevalence of birth defects and additional studies reporting the prevalence of sub types of birth defects among newborn in sub-Saharan African countries included in the systematic review and meta-analysis

Table 1 (suite 1): descriptive summary of 25 studies reporting the prevalence of birth defects and additional studies reporting the prevalence of sub types of birth defects among newborn in sub-Saharan African countries included in the systematic review and meta-analysis

Table 1 (suite 2): descriptive summary of 25 studies reporting the prevalence of birth defects and additional studies reporting the prevalence of sub types of birth defects among newborn in sub-Saharan African countries included in the systematic review and meta-analysis

Table 2: descriptive summary of 4 studies reporting the associated risk factors of birth defects among newborn in sub-Saharan African countries included in the systematic review and meta-analysis

Table 3: table depicting the pooled prevalence of different types of birth defects in sub-Saharan African Countries, 2018

Figure 1: flow chart describing the selection of studies for the systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and associated factors of birth defects among newborn in sub-Saharan African countries; 2018 (identified screened, eligible and included studies); articles may have been excluded for more than one reason

Figure 2: forest plot of the sub-group showing the pooled prevalence of birth defects in sub-Saharan African countries, 2018

Figure 3: forest plot of the sub-group analysis of prevalence of birth defects in sub-Saharan African countries, 2018

Figure 4: forest plot depicting pooled odds ratio (log scale) of the associations between prevalence of birth defects and maternal folic acid supplementation, 2018

Figure 5: forest plot depicting pooled odds ratio (log scale) of the associations between prevalence of birth defects and maternal illness, 2018

Figure 6: forest plot depicting pooled odds ratio (log scale) of the associations between prevalence of birth defects and maternal history of medication, 2018

- DeSilva M, Munoz FM, Mcmillan M, Kawai AT, Marshall H, Macartney KK et al. Congenital anomalies: Case definition and guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine. 2016;34(49):6015. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Organization WH. The Selection and Use of Essential Medicines: Report of the WHO Expert Committee, 2015 (including the 19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines and the 5th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children): WHO. 2015. Google Scholar

- Organization WH. Breastfeeding in the context of Zika virus: interim guidance. 2016. Google Scholar

- Lamichhane DK, Leem J-H, Park M, Kim JA, Kim HC, Kim JH et al. Increased prevalence of some birth defects in Korea, 2009-2010. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2016;16(1):61. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Postoev VA, Nieboer E, Grjibovski AM, Odland JØ. Prevalence of birth defects in an Arctic Russian setting from 1973 to 2011: a register-based study. Reproductive health. 2015;12(1):3. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Czeizel AE, Dudás I, Vereczkey A, Bánhidy F. Folate deficiency and folic acid supplementation: the prevention of neural-tube defects and congenital heart defects. Nutrients. 2013;5(11):4760-75. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Shannon GD, Alberg C, Nacul L, Pashayan N. Preconception healthcare and congenital disorders: systematic review of the effectiveness of preconception care programs in the prevention of congenital disorders. Maternal and child health journal. 2014;18(6):1354-79. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Heymann DL, Hodgson A, Freedman DO, Staples JE, Althabe F, Baruah K et al. Zika virus and microcephaly: why is this situation a PHEIC? The Lancet. 2016;387(10020):719-21. PubMed | Google Scholar

- KIng I. Controlling Birth Defects: Reducing the Hidden Toll of Dying and Disabled Children in Low-Income Countries. 2008. Google Scholar

- Week FAA. Update on Overall Prevalence of Major Birth Defects-Atlanta, Georgia, 1978-2005. Google Scholar

- Garne E, Dolk H, Loane M, Eurocat PAB, On Behalf Of. EUROCAT website data on prenatal detection rates of congenital anomalies. SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England. 2010. Google Scholar

- Organization WH, Society ISC. International perspectives on spinal cord injury: World Health Organization. 2013. Google Scholar

- Mombo LE, Yangawagou-Eyeghe LM, Mickala P, Moutélé J, Bah TS, Tchelougou D et al. Patterns and risk factors of birth defects in rural areas of south-eastern Gabon. Congenital anomalies. 2017;57(3):79-82. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Delport S, Christianson A, Van den Berg H, Wolmarans L, Gericke G. Congenital anomalies in black South African liveborn neonates at an urban academic hospital. South African Medical Journal. 1995;85(1):11-5. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000100. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2003;327(7414):557. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Schumacher M. Undue reliance on I 2 in assessing heterogeneity may mislead. BMC medical research methodology. 2008;8(1):79. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2001;54(10):1046-55. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj. 1997;315(7109):629-34. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Abbey M, Oloyede OA, Bassey G, Kejeh BM, Otaigbe BE, Opara PI et al. Prevalence and pattern of birth defects in a tertiary health facility in the Niger Delta area of Nigeria. International journal of women's health. 2017;9:115. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Anyanwu L-JC, Danborno B, Hamman WO. Birth prevalence of overt congenital anomalies in Kano Metropolis: overt congenital anomalies in the Kano. Nature. 2015;220(25.55):58.97. Google Scholar

- Ekanem TB, Okon DE, Akpantah AO, Mesembe OE, Eluwa MA, Ekong MB. Prevalence of congenital malformations in Cross River and Akwa Ibom states of Nigeria from 1980-2003. Congenital anomalies. 2008;48(4):167-70. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Ekwochi U, Asinobi IN, Osuorah DCI, Ndu IK, Ifediora C, Amadi OF et al. Pattern of Congenital Anomalies in Newborn: A 4-Year Surveillance of Newborns Delivered in a Tertiary Healthcare Facility in the South-East Nigeria. Journal of tropical pediatrics. 2017. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Iroha E, Egri-Okwaji M, Odum C, Anorlu R, Oye-Adeniran B, Banjo A. Perinatal outcome of obvious congenital malformation as seen at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Paediatrics. 2001;28(3):73-7. Google Scholar

- Mukhtar-Yola M, Ibrahim M, Belonwu R, Farouk Z, Mohammed A. The prevalence and perinatal outcome of obvious congenital malformations among inborn babies at Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Kano. Nigerian Journal of Paediatrics. 2005;32(2):47-51. Google Scholar

- Obu HA, Chinawa JM, Uleanya ND, Adimora GN, Obi IE. Congenital malformations among newborns admitted in the neonatal unit of a tertiary hospital in Enugu, South-East Nigeria-a retrospective study. BMC research notes. 2012;5(1):177. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Ochoga M, Tolough G, Michael A, Ikuren I, Shogo A, Abah R. Congenital Anomalies at Benue State University Teaching Hospital, Makurdi, Benue State: A Three-year Review. Google Scholar

- Onankpa B, Adamu A. Pattern and outcome of gross congenital malformations at birth amongst newborns admitted to a tertiary hospital in northern Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Paediatrics. 2014;41(4):337-40. Google Scholar

- Onyearugha C, Onyire B. Congenital malformations as seen in a secondary healthcare institution in Southeast Nigeria. Journal of Medical Investigations and Practice. 2014;9(2):59. Google Scholar

- Ekanem T, Bassey I, Mesembe O, Eluwa M, Ekong M. Incidence of congenital malformation in 2 major hospitals in Rivers state of Nigeria from 1990 to 2003. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2011;17(9):701. Google Scholar

- Muga R, Mumah S, Juma P. Congenital malformations among newborns in Kenya. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development. 2009;9(3). Google Scholar

- Kishimba RS, Mpembeni R, Mghamba JM, Goodman D, Valencia D. Birth prevalence of selected external structural birth defects at four hospitals in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2011-2012. Journal of global health. 2015;5(2):020411. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Ahuka O, Toko R, Omanga F, Tshimpanga B. Congenital malformations in the North-Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo during civil war. East African medical journal. 2006;83(2):95-9. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Kromberg J, Jenkins T. Common birth defects in South African Blacks. South African medical journal= Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde. 1982;62(17):599-602. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Liu KC, Farahani M, Mashamba T, Mawela M, Joseph J, Van Schaik N et al. Pregnancy outcomes and birth defects from an antiretroviral drug safety study of women in South Africa and Zambia. AIDS (London, England). 2014;28(15):2259. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Venter P, Christianson A, Hutamo C, Makhura M, Gericke G. Congenital anomalies in rural black South African neonates-a silent epidemic? South African Medical Journal. 1995;85(1):15-20. Google Scholar

- Ndibazza J, Lule S, Nampijja M, Mpairwe H, Oduru G, Kiggundu M et al. A description of congenital anomalies among infants in Entebbe, Uganda. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 2011;91(9):857-61. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Simpkiss M, Lowe A. Congenital abnormalities in the African newborn. Archives of disease in childhood. 1961;36(188):404. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Nuertey B, Gumanga S, Kolbila D, Malechi H, Asilfi A, Konsosa M et al. External structural congenital anomalies diagnosed at birth in Tamale teaching hospital. Postgraduate Medical Journal of Ghana. 2017;6(1):24-9.

- Adane F, Seyoum G. Prevalence and associated factors of birth defects among newborns at referral hospitals in Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development. 2018;32(3). Google Scholar

- Mekonen HK, Nigatu B, Lamers WH. Birth weight by gestational age and congenital malformations in Northern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015 Mar 29;15:76. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Taye M, Afework M, Fantaye W, Diro E, Worku A. Magnitude of Birth Defects in Central and Northwest Ethiopia from 2010-2014: A Descriptive Retrospective Study. PloS one. 2016;11(10):e0161998. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Mashuda F, Zuechner A, Chalya PL, Kidenya BR, Manyama M. Pattern and factors associated with congenital anomalies among young infants admitted at Bugando medical centre, Mwanza, Tanzania. BMC research notes. 2014;7(1):195. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Kishimba RS, Mpembeni R, Mghamba J. Factors associated with major structural birth defects among newborns delivered at Muhimbili National Hospital and Municipal Hospitals in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania 2011-2012. Pan Afr Med J. 2015 Feb 18;20:153. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Taye M, Afework M, Fantaye W, Diro E, Worku A. Factors associated with congenital anomalies in Addis Ababa and the Amhara Region, Ethiopia: a case-control study. BMC pediatrics. 2018;18(1):142. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Shawky RM, Sadik DI. Congenital malformations prevalent among Egyptian children and associated risk factors. Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics. 2011;12(1). Google Scholar

- Dolk H, Loane M, Garne E. The prevalence of congenital anomalies in Europe. Rare diseases epidemiology. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;686:349-64. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Raza MZ, Sheikh A, Ahmed SS, Ali S, Naqvi SMA. Risk factors associated with birth defects at a tertiary care center in Pakistan. Ital J Pediatr. 2012 Dec 7;38:68. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Cherian AG, Jamkhandi D, George K, Bose A, Prasad J, Minz S. Prevalence of Congenital Anomalies in a Secondary Care Hospital in South India: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of tropical pediatrics. J Trop Pediatr. 2016 Oct;62(5):361-7. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Stevenson AC, Johnston HA, Stewart M, Golding DR. Congenital malformations: a report of a study of series of consecutive births in 24 centres. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1966;34(Suppl):9. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Hoang T, Nguyen PVN, Tran DA, Gillerot Y, Reding R, Robert A. External birth defects in southern Vietnam: a population-based study at the grassroots level of health care in Binh Thuan province. BMC Pediatr. 2013 Apr 30;13:67. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Pasha YZ, Vahedi A, Zamani M, Alizadeh-Navaei R, Pasha EZ. Prevalence of Birth Defects in Iran: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Archives of Iranian Medicine (AIM). 2017;20(6). Google Scholar

- Ofori B, Oraichi D, Blais L, Rey E, Bérard A. Risk of congenital anomalies in pregnant users of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: A nested case-control study. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2006 Aug;77(4):268-79. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Sharma A, Rawat AK. Toxicological consequences of chloroquine and ethanol on the developing fetus. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1989;34(1):77-82. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Nelson MM, Forfar JO. Associations between drugs administered during pregnancy and congenital abnormalities of the fetus. Br Med J. 1971;1(5748):523-7. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Hernández-Díaz S, Werler MM, Walker AM, Mitchell AA. Folic acid antagonists during pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. New England journal of medicine. 2000;343(22):1608-14. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Canfield MA, Anderson JL, Waller DK, Palmer SE, Kaye CI. Folic acid awareness and use among women with a history of a neural tube defect pregnancy--Texas, 2000-2001. MMWR Recommendations and reports: Morbidity and mortality weekly report Recommendations and reports/Centers for Disease Control. 2002;51(RR-13):16-9. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Hall J, Solehdin F. Folic acid for the prevention of congenital anomalies. European journal of pediatrics. 1998;157(6):445-50. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Scholl TO, Johnson WG. Folic acid: influence on the outcome of pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000 May;71(5 Suppl):1295S-303S. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Lawal TA, Adeleye AO. Determinants of folic acid intake during preconception and in early pregnancy by mothers in Ibadan, Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2014 Oct 1;19:113. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Canfield MA, Przybyla SM, Case AP, Ramadhani T, Suarez L, Dyer J. Folic acid awareness and supplementation among Texas women of childbearing age. Prev Med. 2006 Jul;43(1):27-30. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Fernández N, Henao-Mejía J, Monterrey P, Pérez J, Zarante I. Association between maternal prenatal vitamin use and congenital abnormalities of the genitourinary tract in a developing country. J Pediatr Urol. 2012 Apr;8(2):121-6. PubMed | Google Scholar

- De Wals P, Tairou F, Van Allen MI, Uh S-H, Lowry RB, Sibbald B et al. Reduction in neural-tube defects after folic acid fortification in Canada. N Engl J Med. 2007 Jul 12;357(2):135-42. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Moore KL, Persaud TVN, Torchia MG. The Developing Human E-Book: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011. Google Scholar

- Stothard KJ, Tennant PW, Bell R, Rankin J. Maternal overweight and obesity and the risk of congenital anomalies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009 Feb 11;301(6):636-50. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Balsells M, García-Patterson A, Gich I, Corcoy R. Major congenital malformations in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012 Mar;28(3):252-7. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Aschim EL, Haugen TB, Tretli S, Daltveit AK, Grotmol T. Risk factors for hypospadias in Norwegian boys-association with testicular dysgenesis syndrome? International journal of andrology. 2004;27(4):213-21. Google Scholar

- Czeizel AE, Bánhidy F. Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011;23(2):76-81. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Caton AR, Bell EM, Druschel CM, Werler MM, Lin AE, Browne ML et al. Antihypertensive medication use during pregnancy and the risk of cardiovascular malformations. Hypertension. 2009;54(1):63-70. PubMed | Google Scholar

Search

This article authors

On Pubmed

On Google Scholar

Citation [Download]

Navigate this article

Similar articles in

Key words

Tables and figures

Figure 1: flow chart describing the selection of studies for the systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and associated factors of birth defects among newborn in sub-Saharan African countries; 2018 (identified screened, eligible and included studies); articles may have been excluded for more than one reason

Figure 1: flow chart describing the selection of studies for the systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and associated factors of birth defects among newborn in sub-Saharan African countries; 2018 (identified screened, eligible and included studies); articles may have been excluded for more than one reason