A retrospective case series of clinical aspects of the 2007-2008 Ebola virus disease outbreak in Bundibugyo, Western Uganda

Rahel Dubiwak Gemmeda, Margaret Loy Khaitsa, Wamala Joseph Francis

Corresponding author: Margaret Loy Khaitsa, Department of Pathobiology and Population Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, Mississippi State University, Mississippi, 39762, United States of America

Received: 06 Mar 2017 - Accepted: 15 May 2017 - Published: 30 Aug 2017

Domain: Epidemiology,Infectious diseases epidemiology

Keywords: Ebola virus disease, Bundibugyo Ebola virus, prognosis, Ebola Virus Disease

This article is published as part of the supplement Capacity building in Integrated Management of Transboundary Animal Diseases and Zoonoses (CIMTRADZ), commissioned by The Mississippi State University College of Veterinary Medicine.

©Rahel Dubiwak Gemmeda et al. Pan African Medical Journal (ISSN: 1937-8688). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Cite this article: Rahel Dubiwak Gemmeda et al. A retrospective case series of clinical aspects of the 2007-2008 Ebola virus disease outbreak in Bundibugyo, Western Uganda. Pan African Medical Journal. 2017;27(4):22. [doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2017.27.4.12181]

Available online at: https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com//content/series/27/4/22/full

Case series

A retrospective case series of clinical aspects of the 2007-2008 Ebola virus disease outbreak in Bundibugyo, Western Uganda

A retrospective case series of clinical aspects of the 2007-2008 Ebola virus disease outbreak in Bundibugyo, Western Uganda

Rahel Dubiwak Gemmeda1,&, Margaret Loy Khaitsa², Wamala Joseph Francis3

1Department of Veterinary and Microbiological Sciences, North Dakota State University Van Es Hall 1523, Centennial Blvd, Fargo, North Dakota, 58102, United States of America, ²Department of Pathobiology and Population Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, Mississippi State University, Mississippi, 39762, United States of America, 3Epidemiological Surveillance Division, Ministry of Health, Uganda and Consultant Epidemiologist at WHO Country Office Juba, Republic of South Sudan

&Corresponding author

Margaret Loy Khaitsa, Department of Pathobiology and Population Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, Mississippi State University, Mississippi, 39762, United States of America

Introduction: Ebola virus disease is a zoonosis that occurs in tropical rainforests of Africa affecting humans, non-human primates and duikers. In humans, it is transmitted by direct contact with patients or their body fluids. The disease is manifested by fever, bleeding and other nonspecific symptoms. Ebola Virus Disease kills 34% to 88% of the diseased individuals depending on the subtype of the virus. Currently, the treatment for Ebola Virus Disease is under investigation. The purpose of this study is to describe the clinical presentation of the 2007-2008 Ebola Virus Disease outbreak and identify significant predictors of the prognosis of the disease.

Methods: a retrospective case series was done to investigate the demographic characteristics, clinical signs and symptoms that were associated with prognosis of patients in the 2007/2008 Ebola Virus Disease outbreak in Western Uganda. Data from Ugandan Ministry of Health were reviewed and Epi info version 3.5.3 and SAS 9.2 were used to analyze the data.

Results: age of patients had significant association with the prognosis of patients with more fatalities observed among the very young & the elderly. Fever, headache, vomiting, diarrhea and difficulty of breathing were among the signs and symptoms experienced by the patients. Difficulty of breathing and blood in the vomitus also showed significant association with death of patients.

Conclusion: this study indicated that during the 2007-2008 Ebola Virus Disease outbreak in Bundibugyo, Western Uganda, age, blood in vomitus and difficulty of breathing among the clinical presentations, were the significant predictors of the prognosis of the disease.

Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) is an emerging zoonosis that was first recognized in 1976 in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) around the river “Ebola River”, that it is named after [1, 2]. The disease is caused by a virus in the family Filoviridae which are single stranded RNA viruses [3]. As summarized by the Unites States (US) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Ebola virus has five sub-types Ebola Zaire (DRC), Ebola Sudan (Sudan), Ebola Ivory Coast (Ivory Coast), Ebola Bundibugyo (Bundibugyo, Uganda), and Ebola Reston (Reston, USA), all named after places where they were first discovered. The first four sub-types cause hemorrhagic fever in humans [4]. The natural reservoir of EVD is not known for sure but it is suspected to be some species of fruit bats [5]. EVD is one of the most deadly diseases with a case fatality rate (CFR) ranging from 34% to 88% [2, 6]. It is transmitted from person to person through direct contact of blood, tissue, body fluids, and secretions. The virus is also transmitted through contaminated needles and fomites. Direct contact with the possible reservoirs bats, infected primates and duikers is thought to be the common way of transmission for index cases of outbreaks [7]. The incubation period of the disease varies from 2 to 21 days. Some of the clinical manifestations are sudden onset of fever, weakness, headache, vomiting, diarrhea, internal and external bleedings. Currently, many drugs and vaccines which could be used for treatment of Ebola Virus Disease are under investigation [8]. According to the CDC, outbreaks of EVD occurred many times in eastern, central and western Africa [4]. Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, Sudan, Uganda, Republic of Congo, Guinea, Siera Leone, Senegal, and Liberia are some of the countries which have had outbreaks [4]. In Uganda, the first EVD outbreak occurred in 2000 with 425 cases and 224 deaths (CFR 53%) in districts of Mbarara, Gulu and Masindi [9]. The outbreak was caused by Ebola Sudan with an unknown index case and lasted for about 18 weeks [9]. The second outbreak occurred in Bundibugyo district with 192 cases and 39 deaths (CFR 34%). The outbreak was caused by a new strain (Bundibugyo Ebola virus) [6].The third outbreak that involved a single case occurred in May of 2011 in Luwero district, central Uganda in a 12 years old girl who had acute febrile illness with hemorrhagic manifestations and was diagnosed with EVD of the Sudan sub-type. Then two more outbreaks occurred in Uganda in 2012 [4, 10]. As an acute and highly virulent disease, conducting epidemiological and clinical studies during outbreaks is the only possible way to understand the pattern of the disease in humans and to provide information for designing and improving prevention and control methods for EVD. The purpose of this study is to describe the clinical presentation of the 2007-2008 EVD outbreak and identify significant predictors of the prognosis of the disease.

Data source

Epidemiological data collected by Ugandan Ministry of Health (MOH) during the 2007- 2008 EVD outbreak that were on Excel register were reviewed. The data were collected by a team of health workers who were working at health facilities giving service to Ebola patients at Bundibugyo hospital and Kikyo health center in Bundibugyo district in Western Uganda. Approximately 60% of Bundibugyo district is covered by the Rwenzori Mountains and Semliki National Park and Game Reserve, which have a broad range of wildlife, including primates [6]. The district has a population of 253,493 and a population density of 108 persons/km² (9), 1 hospital, and 26 health centers. The main economic activities are cocoa farming, fishing, and tourism [6]. Hunting of wild animals is common among settlements near the national park [6]. The data were collected from November 29, 2007 to February 20, 2008 according to the case definition set by the epidemic response team. Detailed information on data collection and laboratory tests used was published earlier [6]. Briefly, Village health teams conducted active searches in the communities through daily door-to-door visits in their respective villages while investigation teams of local and international experts reviewed case notes at health facilities and verified suspected cases reported by the village health teams [6]. The case definitions and categorizations used in this study were also taken from previously published study [6]. In total, there were 192 suspected EHF cases. Of these, 42 (22%) were laboratory confirmed as positive for a novel Ebola virus species (Bundibugyo ebolavirus); 74 (38%) were probable, and 76 (40%) were laboratory negative and classified as non-cases [6]. This study utilized only 116 individuals who were categorized as probable and confirmed cases. The study was exempt from ethical review as it was de-identified data with no names and physical address.

Data analysis Descriptive epidemiology: age, sex, occupation, clinical presentations and outcome of the illness were among the variables used to describe cases by humans. For purposes of data analysis, age was divided into three categories (0-10, 11-40, 41-70) informed by previous studies conducted earlier [6] and guided by the age structure for Bundibugyo district obtained from the Uganda population and housing census report of 2002 from Uganda Bureau of Statistics. Epi info software version 3.5.3 and SAS 9.2.were used for further analysis.

Chi square analysis

Chi square analysis was performed to determine the association between demographic characteristics and clinical features of patients and prognosis of the cases. Outcome of the disease (survival or death) was used as dependent variables and demographic characteristics and clinical features were used as independent variables. The age group of cases was categorized into two groups (11-40 vs. 41-70). Children under the age of 10 were excluded from the two age groups. Cases with missing information regarding the clinical features were excluded from the study as well. The chi square analysis was done using SAS 9.2.

Logistic regression

Logistic regression was used to analyze the significant demographic characteristics and clinical presentations associated with prognosis. Forward selection procedure was used for analysis and the data were analyzed using SAS system. P value of < 0.05 was used as benchmark for significance.

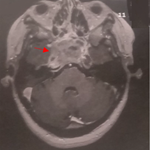

All the cases were from Bundibugyo district in western Uganda (Figure 1). Illnesses in 192 persons met the definition for suspected EHF. Of these, 42 (22%) were laboratory confirmed as positive for a novel Ebola virus species (Bundibugyo ebolavirus); 74 (38%) were probable, and 76 (40%) were laboratory negative and classified as non-cases [6]. This study utilized only 116 confirmed and probable EHF cases. The index case of the outbreak was presumably a 26 years old pregnant woman who experienced febrile illness followed by preterm delivery. The index patient and her family members who cared for her died during the outbreak [6]. Hunting spears were found at her home, but hunting as a practice was denied [6].

Distribution of the outbreak by humans

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the confirmed and probable EVD cases. The age range among the cases was 3 weeks to 70 years, and the majority (56%) of cases were male. Most cases (35%) were farmers followed by health care workers (14%).

Clinical presentations

Fever (97%), headache (89%), abdominal pain (88%) and vomiting (84%) were the most common signs and symptoms experienced by the patients (Table 2).

Determinants of prognosis

The age specific case fatality rate was higher among age groups 0-10, 51-60 and 61-70 years, 4/6 (66%), 8/11 (72.7%) and 3/5 (60%) respectively and it was lowest 4/20 (20%) among the age group 11-20 years. For the age group 0-10 all the deaths occurred among children under the age of 5 years. The mean age of survivors was 32 years while that of succumbed patients was 38 years. The mean age of succumbed patients was significantly higher than the mean age of survivors X² = 5.17, P < 0.023. Age group was significantly associated with prognosis of patients in logistic regression model (OR 12.30, P = 0.0021). The Logistic regression utilized 113 out of 116 observations in the data set. The age group (11-40 years) had better survival than the young cases (0-10) and the older cases (41-70 years) so was used as the reference group. The young age group (0-10 years) were more likely to die compared to the 11-40 age group (reference group) (OR 14.7, 95% CI [1.52-141.18], P = 0.0739). Also, the older cases (40-70) were more likely to die compared to the 11-40 reference group (OR 3.67, 95% CI [1.56-8.62], P = 0.0393). The sex specific CFR was 16/51 (31%) for female and 23/65 (35%) for male. The sex specific CFR was not significantly different for female and male patients (X² = 0.19, P<0.66). Of 108 cases of EVD 59(54.6%) experienced difficulty of breathing. In bivariate analysis difficulty of breathing was found to have a significant association with the death of patients (X² = 8.1, OR 3.6 95% CI [1.4-9.2], P < 0.004). In logistic regression model, the odds of having difficulty of breathing was four times higher among patients who died compared to patients who lived (OR 4.20, 95% CI [1.62-10.92], P = 0.0032). This analysis utilized 106 observations out of 113 read. The data on difficulty of breathing was missing for 10 individuals out of 116. Having blood in vomitus was significantly associated with death (OR 3.38, 95% CI [1.32-8.65], P = 0.0109). Other clinical signs and symptoms did not show significant association with prognosis. In the multivariable model that included children 0-10 years, age and blood in the vomitus were the only two variables that were significant predictors of death.

This EVD outbreak occurred in Bundibugyo district, which is located in western Uganda and shares a border with Democratic Republic of Congo, where previous outbreaks of EVD occurred [2, 6]. EVD outbreaks occur in humid tropical rain forests of Africa [11]. The district shares ecological and geographical similarity with places where previous outbreaks occurred [6, 11]. The outbreak affected every age group. Even though, the number of cases was very few in the age groups 0-10, and 51 and above, the death rates were higher in those age groups. As in previous outbreaks [12], there was higher number of cases in the age group 11-50 years, but this group experienced a lower death rate compared to the elderly and young children. A previous study reported that being above the age of 18 years was one of the risk factors for EVD intra-familial transmission [12]. The higher number of cases in the age group 11-50 might be due to the exposure of those groups to the risk factors of EVD, like attending funerals, caring for patients traveling and occupational exposures [7]. In this outbreak, only few children acquired EVD, and that was in agreement with previous studies [12, 13]. The death rate varied among the age groups, with relatively higher death rate among the elderly (> 51years). This finding could be explained by lower innate and humoral immunity level and/or presence of other chronic diseases associated with old age [14, 15]. Similarly, in agreement with previous outbreaks [13] higher death rate was observed among children under the age of 5years compared to other age groups. Those two age groups may need special attention and protection during outbreaks not because of the incidence rate but due to higher death rates. Unlike other outbreaks where women were affected more than men [2, 16], in the Bundibugyo outbreak less number of women acquired and died of EVD. The control measures put in place by the outbreak response team might have shielded women and decreased their risk of acquiring the disease. Women have previously been reported to have higher infection rates due to their cultural role in caring for the sick and preparing bodies for funerals [17].

Predictors of prognosis: the age group of patients was significantly associated with outcome of EVD infection. Other studies also reported age to be associated with the survival of patients. The mean age of fatal cases was significantly higher than the age of the survivors [18, 19]. Therefore, elderly patients need more protection during outbreaks. Among the clinical presentations, difficulty of breathing was the best predictor of the outcome of the disease. Even though, the pathophysiology of shortness of breath was not fully understood, other studies also found out difficulty of breathing as one of the factors that predict the prognosis of patients [20, 21]. However, in the 2014 Sierra Leone Ebola Virus Disease outbreak, weakness, diarrhea and dizziness were the clinical signs that were associated with death [22]. In general, there could have been other significant confounders of risk factors for death among cases. For instance, in Uganda, the nutritional status of the population, particularly children and women is poor and has been identified as a major health problem in Uganda. The health status indices of Uganda are still very poor, comparable with the average for sub-Saharan Africa [23]. Health care infrastructure in Uganda is still inadequate and poor especially in rural areas and health care delivery coverage was estimated at 72% [23]. In spite of modest improvements in government expenditure on health, overall investment in health remains low; the referral system remains unsatisfactorily weak because of shortages of equipment, especially ambulance and communication equipment. The country continues to experience a shortage of trained workforce. For instance, as of 2003 with a population of 24 million people, Uganda had only 2209 medical doctors registered with the Uganda Medical and Dental Practitioners´ council. The doctor to population ratio was at 1:12,000, and not all these doctors were Ugandans. About 25% of the doctors registered with the medical council were foreigners. The most rare cadres in the Country included; Pharmacists whose availability is about 30% of the required number. Others include Physiotherapists, Dental Surgeons, Radiographers, Laboratory technicians and Anaesthetic assistants. Private health infrastructure is more developed and concentrated in urban centres than in the rural areas where most of the population, including the poorest quintiles lives. Hence, ready access for health services in times of dire need by the rural communities remains a big challenge [23]. The major challenges affecting the health system are the lack of resources to recruit, deploy and retain human resources for health, particularly in remote localities; ensuring quality of the health care services delivered; ensuring reliability of health information in terms of the quality, timeliness and completeness of data; and reducing stock-out of essential/tracer medicines and medical supplies. The emergence of antimicrobial resistance due to the rampant inappropriate use of medicines and irrational prescription practices and the inadequate control of substandard, spurious, falsely labelled, falsified or counterfeit medicines are also key problems in the sector [24]. Lastly, Bundibugyo district where the Ebola outbreak occurred shares borders with the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) which has similar challenges to those described for Uganda and experiences Ebola outbreaks. In mid-September 2007, the Ministry of Health of the DRC confirmed an outbreak of Ebola haemorrhagic fever in some remote communities in the province of Kasai [25]. On November 5, 2007, the Uganda Ministry of Health (UMOH) received a report of the deaths of 20 persons in Bundibugyo district, western Uganda. However, UMOH had received initial reports of 2 suspected cases of a febrile diarrheal illness on August 2, 2007. A UMOH team investigated these 2 cases, but the findings were not conclusive because of inadequate in-country laboratory capacity. In the second report, ill persons had an acute febrile hemorrhagic illness, and tests conducted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA, USA) confirmed the illness as EHF on November 29, 2007. Therefore, it is possible that the index case in this outbreak may have had contact with cases from the DRC.

The 2007-2008 EVD Outbreak in Bundibugyo, Western Uganda, affected every age group and both sexes with more deaths among the very young (0-10) and the elderly (41-70) compared to the 11-40 year old cases. Of the many clinical symptoms experienced by the patients, difficulty of breathing and presence of blood in the vomitus were the best predictors of the outcome of disease.

What is known about this topic

- EVD is one of the most deadly diseases with case fatality rates of 34% to 88%;

- Some of the clinical manifestations are sudden onset of fever, weakness, headache, vomiting, diarrhea, internal and external bleedings;

- EHF is transmitted from person to person through contact with blood, tissue, body fluids, and secretions of infected persons: it is also transmitted through contaminated needles and fomites: direct contact with bats, infected primates and duikers is thought to be the common way of transmission for index cases of outbreaks.

What this study adds

- Even though Ebola affects all age groups, patients who were older than 40 years of age had poor prognosis;

- Younger patients in the age group 11 to 40 years had good prognosis compared to older patients;

- Patients who had difficulty of breathing had poor prognosis compared to patients who did not have difficulty of breathing.

The authors declare no competing interest.

Rahel Dubiwak Gemmeda contributed in the conception and design of the study, analysis of data, interpretation of data and writing the article. Margaret Loy Khaitsa contributed in the acquisition of funding, conception and design of the study, revision of the article and the final approval of the version to be published. Wamala Joseph Francis contributed in the acquisition of data, conception and design of the study and revision of the article. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of this manuscript and have equally contributed to its content and to the management of the case.

The authors wish to thank all health workers who collected the information used for this study; the Ugandan Ministry of Health for providing the data; and the US Department of Agriculture for funding the Master of Science degree in International Infectious Disease Management and Biosecurity program at North Dakota State University.

Table 1: socio-demographic characteristics of EVD cases in Bundibugyo, Uganda, August 2007-January 2008 (N = 116)

Table 2:

clinical presentations of Ebola virus disease cases in Bundibugyo, Uganda, August

2007 to January 2008 (N = 116)

Figure 1: spatial distribution

of Ebola virus disease in Bundibugyo, Uganda, August 2007 to January

2008, (N=114)

- Leroy Eric, Pierre Rouquet, Pierre Formenty, Sandrine Souquiere, Annelisa Kilbourne, Jean-Marc Froment, Magdalena Bermejo et al. Multiple Ebola virus transmission events and rapid decline of central African wildlife. Science. 2004 Jan 16; 303(5656): 387-90. PubMed | Google Scholar

- World Health Organization. Ebola hemorrhagic fever in Zaire 1976. Bull World Health Organ. 1978; 56(2): 271-93. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Hans-Dieter Klenk, Heinz Feldmann. Ebola and Marburg viruses: Molecular and cellular biology. Horizon Bioscience: Norfolk. 2004; pp 306-307. Google Scholar

- Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever information packet. Updated 2015 Aug; Cited 2015 Jun 10. Accessed on 15 May 2017.

- Leroy Eric, Brice Kumulungui, Xavier Pourrut, Pierre Rouquet, Alexandre Hassanin, Philippe Yaba, André Délicat, Janusz Paweska, Jean-Paul Gonzalez, Robert Swanepoel. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature. 2005 Dec 1; 438(7068): 575-6. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Wamala Joseph, Luswa Lukwago, Mugagga Malimbo, Patrick Nguku, Zabulon Yoti, Monica Musenero Jackson Amone, William Mbabazi, Miriam Nanyunja, Sam Zaramba, Alex Opio, Julius Lutwama, Ambrose Talisuna, and Sam Okware. Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever: Associated with novel virus strain, Uganda, 2007-2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010 Jul; 16(7): 1087-1092. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Paolo Francesconi, Zabulon Yoti, Silvia Declich, Paul Awil Onek, Massimo Fabiani, Joseph Olango, Roberta Andraghetti, Pierre Rollin, Cyprian Opira, Donato Greco, and Stefania Salmaso. Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever transmission and risk factors of contacts, Uganda. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003 Nov; 9(11): 1430-1437. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Goeijenbier Marco, Van Kampen JJ, Reusken CB, Koopmans MP, Van Gorp EC. Ebola virus disease: a review on epidemiology, symptoms, treatment and pathogenesis." Neth J Med. 2014 Nov; 72(9): 442-8. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Lamunu Margaret, Lutwama Julius, Kamugisha Jimmy, Opio Alex, Nambooze Josephine, Ndayimirije Nestor, Okware Sam. Containing a hemorrhagic fever epidemic: the Ebola experience in Uganda (October 2000-January 2001). Int J Infect Dis. 2004 Jan; 8(1): 27-37. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Trevor Shoemaker, Adam MacNeil, Stephen Balinandi, Shelley Campbell, Joseph Francis Wamala, Laura McMullan, Robert Downing, Julius Lutwama, Edward Mbidde, Ute Ströher, Pierre Rollin, Stuart Nichol. Reemerging Sudan Ebola Virus Disease in Uganda, 2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012 Sep; 18(9): 1480-3. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Peterson Townsend, John Bauer, and James Mills. Ecologic and Geographic distribution of Filovirus Disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004 Jan; 10(1): 40-7. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Dowell Scott, Rose Mukunu, Thomas Ksiazek, Ali, Khan, Pierre Rollin, Jarhling Peters. Transmission of Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever: A Study of Risk Factors in Family Members, Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo 1995. J Infect Dis. 1999 Feb; 179 Suppl 1: S87-91. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Mupere Ezekiel, Kaducu OF, Yoti Zabulon. Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever among hospitalized children and adolescents in northern Uganda: Epidemiologic and clinical observations. Afr Health Sci. 2001 Dec; 1(2): 60-5. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Plowden Julie, Renshaw- Hoelscher Mary, Engleman Carrie, Katz Jacqueline, Sambhara Suryaprakash. Innate immunity in aging: impact on macrophage function. Aging Cell. 2004 Aug; 3(4): 161-7. PubMed | Google Scholar

- McGlauchlen Kiley, Vogel Laura. Ineffective humoral immunity in the elderly. Microbes Infect. 2003 Nov; 5(13): 1279-84. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Okware Sam, Omaswa Francis, Zaramba Sam, Opio Alex, Lutwama Julius J, Kamugisha Jimmy, Rwaguma EB, Lamunu Margaret. An outbreak of Ebola in Uganda. Tropical Trop Med Int Health. 2002 Dec; 7(12): 1068-75. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Barry Hewlett, Richard Amola. Cultural contexts of Ebola in Northern Uganda. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003 Oct; 9(10): 1242-8. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Sadek Ramse, Khan Ali, Stevens Gary, Peters Jarhling, Ksiazek Thomas. Ebola hemorrhagic fever, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1995: determinants of survival. J Infect Dis. 1999 Feb; 179 Suppl 1: S24-7. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Khan Ali, Tshioko Kweteminga, Heymann David, Guenno Bernard, Nabeth Pierre, Kerstiëns Barbara, Fleerackers Yon, Kilmarx Peter, Rodier, Guenael, Nkuku Okumi, Rollin Pierre, Sanchez Anthony, Zaki Sherif, Swanepoel Robert, Tomori Ovewale, Nichol Stuart, Peter Jarhling, Muyembe-Tamfum, Ksiazek Thomas. The reemergence of Ebola hemorrhagic fever, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1995. J Infect Dis. 1999 Feb; 179 Suppl 1: S76-86. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Barry Moumié, Abdoulaye Touré, Fodé Amara Traoré, Fodé-Bangaly Sako, Djibril Sylla, Dimai Ouo Kpamy, Elhadj Ibrahima Bah, M´Mah Bangoura, Marc Poncin, Sakoba Keita, Thierno Mamadou Tounkara, Mohamed Cisse, Philippe Vanhems. Clinical predictors of mortality in patients with Ebola virus disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Jun 15; 60(12): 1821-4. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Bordes Julien, Karkowski Ludovic, Cournac Jean Marie, Gagnon Nicolas, Billhot Magali, Rousseau Claire, De Greslan Thierry, Cellarier Gilles. Dyspnea and Risk of Death in Ebola Infected Patients: Is Lung Really Involved?. Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Sep 1; 61(5): 852. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Schieffelin, John S, Jeffrey Shaffer G, Augustine Goba, Michael Gbakie, Stephen Gire K, Andres Colubri, Rachel Sealfon SG et al. Clinical illness and outcomes in patients with Ebola in Sierra Leone. N Engl J Med. 2014 Nov 27; 371(22): 2092-100. PubMed | Google Scholar

- World Health Organization Country Cooperation Strategy Uganda 2016-2020. WHO-Regional Office for Africa. Accessed on 15 May 2017.

- Health System Profile for Uganda. World Health Report. 2000; Accessed on 15 May 2017.

- The World Health Organization (WHO). Outbreak of Ebola haemorrhagic fever in DRC. 2007. Cited May 15, 2017. Accessed on 15 May 2017.